It has now been five months since the conservative Perikatan Nasional (PN) administration wrested control of Malaysia from its reformist opponent Pakatan Harapan, a coalition beset by petty and no less public squabbles from the first day of its mandate in May 2018 till its collapse 22 months later.

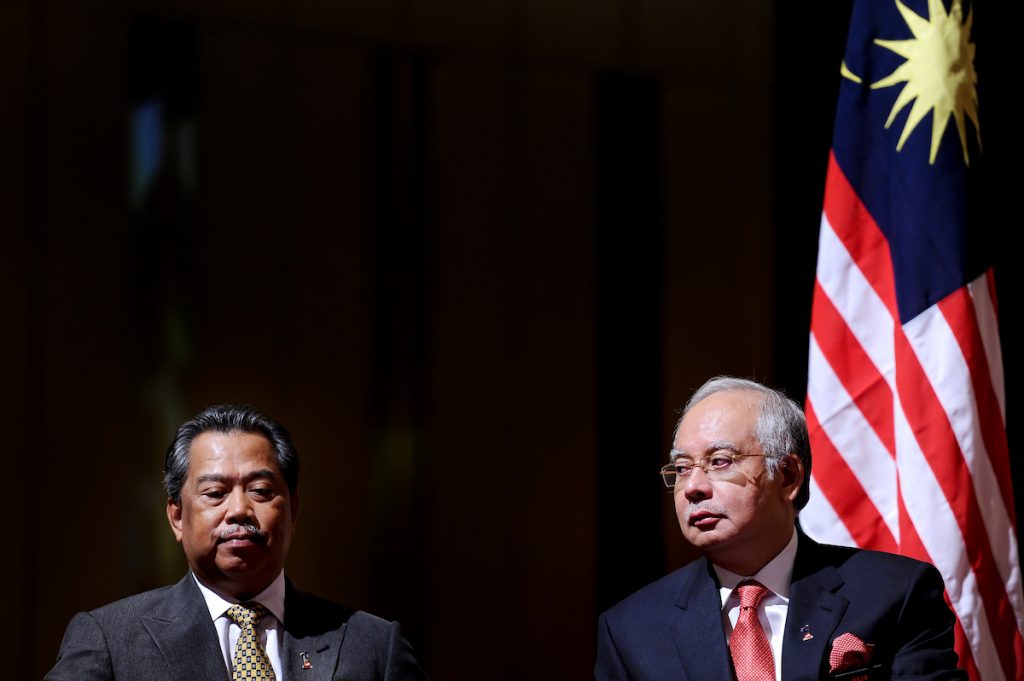

Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin is determined to cement his grip on the country, despite his wafer-thin majority in Parliament.

However, Muhyiddin is facing a major headache in how to control the narrative and press home his authority with the people, the majority of which did not vote for his government.

In the 60 years of the Barisan Nasional coalition, which came to an ignominious end under former Prime Minister Najib Razak and a whale of a corruption scandal in 2018, the Cabinet enjoyed enormous control of the media.

Aside from state radio and television channels, ruling parties owned most of the major domestic news outlets, through which they guaranteed to shout down any voice of opposition from independent portals.

If that failed, the threat of hefty lawsuits for eight-figure sums or stiff prison sentences was usually enough to keep dissenting editors in line.

However, the media landscape in Malaysia has changed a lot since 2018. The government no longer controls its so-called private media interests.

Malay nationalist party Umno — the driving force of Barisan Nasional — once bankrolled Media Prima, a behemoth of an organisation operating an array of television and radio stations, newspapers, and magazines in English, Bahasa Malaysia and Chinese.

For decades, the government was able to use this apparatus to project itself as a benevolent organisation, working overtime to provide for the nation.

Ministers were often afforded almost deity-like status, literally swooping in to solve problems and avert disaster, while graciously accepting thanks from grateful voters. The rhetoric was sometimes not far removed from that north of the 38th parallel.

No more. After losing the 2018 general election, Umno’s funding dried up, meaning it could no longer pour money into its media juggernaut.

This led to the sale of Media Prima and, crucially, the collapse of party mouthpiece Utusan Malaysia in 2019.

The upshot is that since February, the media battlefield is already scarred. Cabinet members used to the warm blanket of zero accountability have already been caught off-guard by news portals, hounding them for gaffes and blunders for which they would previously have expected adulation or at the very least a guaranteed opportunity to “clarify” their mistake.

Defence Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob resorted to Barisan-era press briefings from the moment he took office. Some of his colleagues have since followed suit.

Only state media are permitted to ask questions, which have been vetted by his office in advance and with enough time for Ismail Sabri to come up with what he believes to be incisive and intelligent responses.

Independent or foreign media are ignored or barred from attending in the first place.

Meanwhile, the government has demonstrated that it is willing to use what legislation remains to keep the press in check, detaining journalists and production teams for a variety of perceived slights of its policies.

However, earlier this month, the press learnt that Minister of Communications and Multimedia Saifuddin Abdullah was leading the plans to take things up a notch.

A new propaganda unit — modelled on the infamous Special Affairs Department (known by its Malay acronym, Jasa) — has just been formed.

Malaysians have a right to be nervous. Back in the day, Jasa’s function was two-fold.

On one hand, it was to provide PR spin to government policies and generally paint the work in a positive light — here and overseas — making sure the world at large saw the “truly Asia” image, a melting pot of cultures and so on.

Yet the role for which Jasa achieved notoriety in Malaysia held an ultimately more sinister purpose.

From its inception, it organised and ran smear campaigns targeting the opposition DAP party and its leaders.

We are not talking about digging out the occasional skeleton in an MP’s closet, like an indiscrete mistress or a drink problem. These were systematic and sustained attacks designed to fuel animosity between the ethnic Chinese and Malay communities, usually without foundation.

Ironically, despite Barisan Nasional’s key policy of racial discrimination, Jasa would portray the DAP as a deeply racist and misogynist Chinese party with an agenda to marginalise ethnic Malays.

In the early years, Jasa’s role was not too taxing, given the DAP’s lack of size and that it posed little threat in Parliament.

However, as opposition to Barisan Nasional grew, so did Jasa’s attempts to discredit anyone who stood in the way of the government, ramping up when Anwar Ibrahim fell from grace as Umno’s golden child in the late 1990s to lead the opposition and take a sizeable chunk of the Malay community with him.

Even though the true extent of Jasa’s programs have never been made public, it is widely believed that in the run-up to the 2018 election it was instrumental in fuelling a series of attacks on DAP leader Lim Guan Eng and his father Kit Siang — a semi-retired veteran politician and now “adviser” to the DAP — accusing them of everything from corruption to involvement in organised crime.

Meanwhile, Jasa organised a series nationwide talks to “correct” the misperception of the 1MDB scandal by painting it as a DAP conspiracy to overthrow the government, while the department sought to secure Najib’s position at all costs, despite overwhelming and public evidence to the contrary.

Attacks on politicians aside, Jasa was equally notorious for infiltrating the primary and secondary school system — despite the existence of multiple laws stating any politicking to children was strictly off limits.

At the 2013 and 2018 general elections, the government saw nothing wrong with schoolchildren as young as six parading around schoolyards in Barisan Nasional paraphernalia. Apparently, the little ones were exercising their right to free speech.

While the new Jasa is operating with a skeleton crew of 50, initial plans are to quickly ramp this complement up to 1,000 people with offices in the Ministry of Communications and Multimedia already set aside.

If indeed the new organisation is to pick up where Jasa left off, then it creates an enormous headache to the political opposition and even media outlets.

Such is the level of suspicion that there are whispers the new Jasa has already been hard at work.

In June, police called opposition MP Hannah Yeoh to federal headquarters in Kuala Lumpur for questioning after a tweet on her official account inferring Muhyiddin’s government supported child marriage triggered outrage.

While ministers stomped feet, dangled the proverbial noose and demanded Yeoh be hit with sedition charges, the police eventually discovered the account had been hacked by a pro-government group, which had then planted the tweet.

Even if Jasa did not instigate this attack, the purpose does have an eerie familiarity to it and one, with the new unit gearing up to join the fight, we shall certainly see more of in future.

Gareth Corsi is a freelance journalist based in Malaysia. The views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of LiCAS.news.