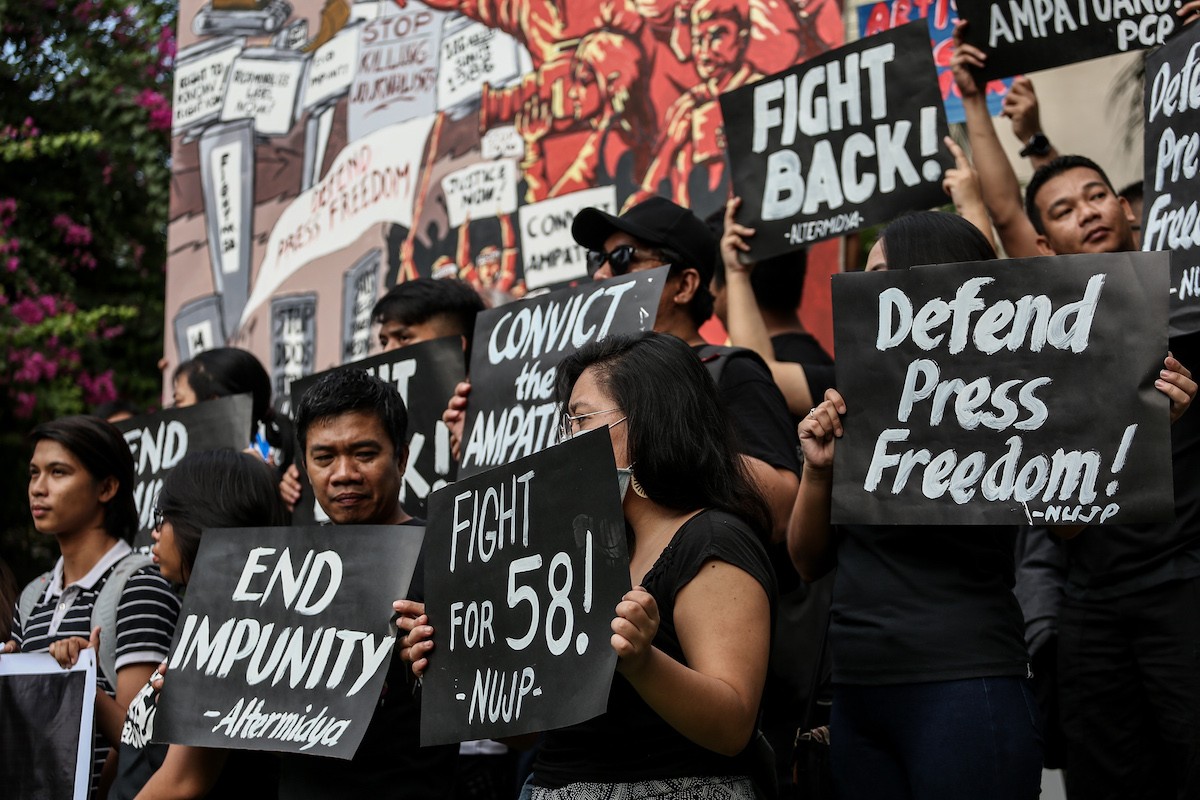

The news of the unspeakable slaughter echoed across every channel when 58 people, 32 of whom were journalists, were killed in the southern Philippines on the morning of Nov. 23, 2009.

I was just 12 years old when the carnage was unleashed. I was old enough to know that it was evil, yet still too young to understand just how far things can go.

It was only when I wrote about the massacre’s seven year observance that I was confronted with what appeared to be the definitive end of press freedom — along with my optimism.

I remember lawyer Romel Bagares, who helped prosecute the perpetuators of the massacre, saying that “ultimate justice is still on the horizon”, even though we don’t have a “God’s eye point of view.”

I found his words frustrating. How can a lawyer believe that one doesn’t get full justice in this life?

Justice it seems, is always proximate. The phrase “proximate justice” was coined by Steven Gerber of the Washington Institute.

He wrote: “When we pray, ‘Your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven,’ we are yearning for the way things ought to be, and someday will be — even as we give ourselves to what can be in a world where evil persists, sometimes very malignantly.”

His idea refers to the acceptance that justice in this world will always be incomplete.

It is making peace with the reality that something is better than nothing. It is learning to be content with some justice, some hope, and some mercy.

And yet it is frustrating still, because those 58 people who were killed deserve something more.

Ten years after that unthinkable massacre, another unthinkable event occurred — on Dec. 19, a verdict was handed down in the decade-long trial.

Of the 197 suspects charged, 80 still remain at large, while 56 were acquitted and a total of 43 were convicted, including scions of the powerful Ampatuan clan who, witnesses claimed, were the masterminds of the crime.

Eight members of the clan were found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment with no possibility of parole.

It might be “acceptable” for a nation that has been waiting years for the trial to come to an end, but not enough for the victims’ families who were expecting all the guilty to be brought to justice.

All the same, the lawyers for the families see the result as a “victory.”

“Let us not see it through the numbers. It’s true that we can’t get absolute justice. We can’t always take back what we have lost,” said lawyer Rachel Pastores.

“The families will always be incomplete, but we should see that the struggles we had to endure for ten years resulted in good things,” she said.

Theodre Deatherage of the Washington Institute related the yearning for justice to Advent.

“Advent teaches us how to live as we wait. To know that because the world’s brokenness, as well as our own, breaks the heart of God, it must break our hearts, too,” he wrote.

“It implicates us in the way things turn out and teaches us to live differently, to fully embrace values of that kingdom which has come but not yet fully. It affirms our hearts’ longing for rescue, our cry, ‘O come, Emmanuel, and ransom us’.”

It is difficult to make sense and peace out of “proximate justice,” the only justice we can get now.

Yet, there is comfort in the idea of pursuing true justice, the one that is to be fulfilled only by God— to believe that heaven can turn agony into eternal bliss.

It is no small thing to ask the families of the victims and more so, those of Bebot Momay — the 58th victim in the gruesome massacre whose case was dismissed due to lack of “corpus delicti” — to make peace with proximate justice.

There are stories so unimaginable they make us lose hope. Through proximal justice, however, as the Irish poet Seamus Heaney once wrote: “the longed-for tidal wave of justice can rise up and hope and history rhyme.”

I have come to realize it is through “proximate justice” that we begin again to believe that there’s a much bigger pair of hands working on true justice, and it takes so much faith to know that it is only through those hands that the universe is to be made right.

Marielle Lucenio reports for LICAS.News in Manila. The views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of LICAS News.