From behind bars, Philippine senator and human rights campaigner Leila de Lima is running for re-election in an against-the-odds campaign that gives her the chance to once again “go after” President Rodrigo Duterte.

De Lima was one of the most vocal and powerful local critics of Duterte after he took power in 2016 and launched a deadly drug war — until he and his allies tried to stifle her.

But despite being forced from the Senate and into a jail cell for the past five years on drug trafficking charges she and human rights groups call a mockery of justice, de Lima has not been “destroyed” as Duterte vowed.

Instead, the 62-year-old is running again for the Senate in May’s national elections, determined to continue her campaign against him.

“I am running because, to put it plainly, my work is not done,” she told AFP in handwritten notes on Senate stationery sent from Manila’s national police headquarters, where she is being held.

“I was jailed because I fought for truth and justice against tyranny and impunity. I was not wrong to do so and I will keep fighting to prove that what I have been fighting for is worth the sacrifice.”

Before her arrest on February 24, 2017, de Lima had spent a decade investigating “death squad” killings allegedly orchestrated by Duterte during his time as Davao City mayor and then in the early days of his presidency.

She conducted the probes while serving as the nation’s human rights commissioner, then from 2010 to 2015 as justice secretary in the Benigno Aquino administration that preceded Duterte’s rule.

De Lima won a Senate seat in 2016, becoming one of the few opposition voices as the populist enjoyed a landslide win.

But Duterte then accused her of running a drug trafficking ring with criminals inside the nation’s biggest prison while she was justice secretary.

The charges were “an act of vengeance” by Duterte to silence her and warn others not to oppose him, said de Lima, who is not allowed bail.

But de Lima hopes she will soon get justice.

Duterte, constitutionally barred from seeking re-election and facing an international probe into his drug war, will lose protection from criminal charges when he leaves office.

“Justice for me is the dismissal of my cases and the prosecution of Duterte and all those who knowingly fabricated and filed fake charges against me,” she said.

‘I’m stronger than I thought’

De Lima is being held in a compound for high-profile detainees, rather than one of the Philippines’ notoriously overcrowded jails.

Her relatively comfortable conditions give her access to outdoor space where she can exercise, tend a small garden and feed more than 10 stray cats.

She is allowed newspapers, has a collection of books given to her by friends, and a Bible that she reads in the evening.

But it is a solitary life.

Before the pandemic she was allowed to see “almost anyone,” she said. Now, she is largely limited to brief visits from her two sons, lawyers, doctors, priests and selected staff.

De Lima, whose marriage was annulled, has not seen her teenage grandchildren in two years, nor her ailing 89-year-old mother in more than three years.

She still works, but with no access to a mobile phone or internet, she cannot participate in Senate debates and hearings.

Instead, she handwrites messages, letters and other documents that her aides pick up.

Routine keeps her sane.

“I learned not to entertain negative thoughts and instead think of my family and the people who believe in me and are fighting with me,” she said.

“I’m much stronger than I thought.”

‘Crimes against humanity’

Since her arrest, one of the three charges against her has been dismissed and two prosecution witnesses have died.

That her court cases have dragged on for so long is not unusual in the Philippines, where even minor cases take years to work their way through the creaky justice system.

COVID-19 has made the process even slower.

De Lima said she is optimistic that no matter who succeeds Duterte, she will be freed soon afterwards.

The next justice secretary “will not have the motivation to continue fabricating evidence against me,” she said.

And she said she had no regrets in seeking to shine a light on Duterte.

“A public official like him who has committed crimes against humanity should be brought to justice,” she said.

At least 6,225 people have died in anti-drug operations since July 2016, according to the latest official Philippine data. Rights groups say the number is in the tens of thousands.

De Lima said her run for a second Senate term is driven by a desire to “help salvage” human rights, democracy and rule of the law in the country — but also revenge.

“I also want to have the opportunity to go after Duterte and all those responsible for my fate, aside from making them accountable for the thousands of murders they have committed and the billions they have plundered,” she said.

But de Lima conceded winning one of the 12 Senate seats would be hard, and polls show she is unlikely to succeed.

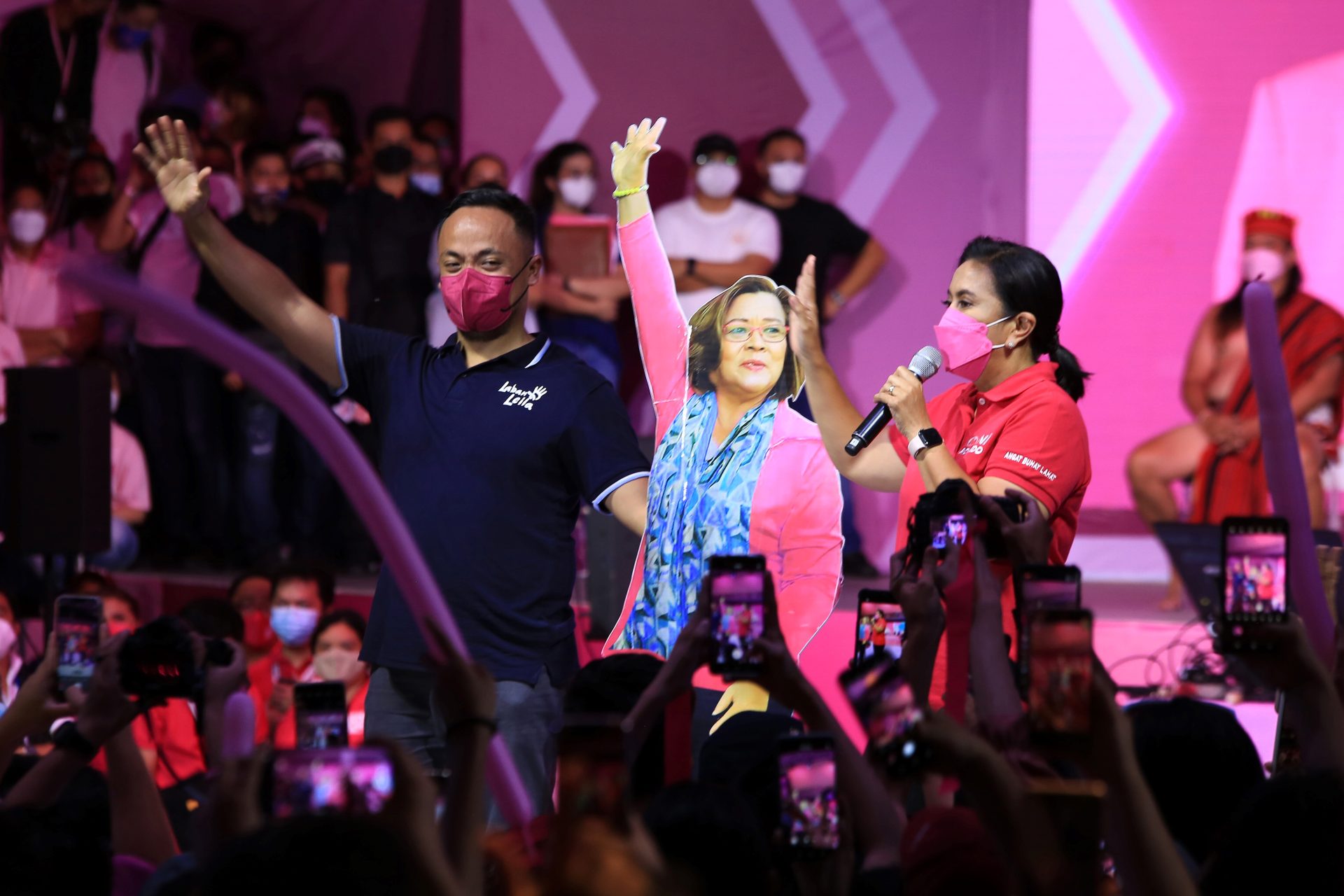

While she was allowed to record campaign videos in late December, she has to rely on proxies to attend rallies — and whatever radio and television advertising she can afford.

Yet she remains characteristically defiant.

“I draw strength from the truth of my innocence,” she said.