Many people still could not “move on,” much less “move forward,” after the Philippine May 9 elections. Some have cried for many nights. Others did not go to work many days after. Still some others did not want to see friends; or many have “unfriended” those who still talk ill and gaslight them.

In my attempt to sort things out and discern many conflicting voices, I needed to listen to voices within me and experiences from the ground. There is one group whom I have been following and supporting from the start of the campaign until the end. I even did a webinar for them just three days before the elections. They are composed of talented and intelligent young people, some young professionals, others still in school. But with them are poor ordinary mothers and fathers who were just convinced that things cannot go on this way, that change is necessary.

In a town of more than 30,000 people, this small group of ordinary citizens banded together without party support and political machinery since their mayoral candidates — three or four of them — all supported BBM (Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos). With few friends here and abroad, this little group went house to house each day during the campaign to convince people about the Leni-Kiko (Leni Robredo-Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan) candidacy with literally nothing except their convictions, good will and few collaterals. No one party did so; only this small group of volunteers.

Their questions are also mine. What happened? How should we understand what happened? Is that all that there is to it? Where do we get resources — internal and external — to move forward? We spent one afternoon to process the questions ourselves and try to sort things out.

As I listened to them explain it to themselves, and assess other voices beyond theirs, I can group four stands of explanation.

- ELITE DEMOCRACY DISCOURSE

One popular explanation can be called the “elite democracy” discourse. Marcos and (President Rodrigo) Duterte apologists came out with this narrative right after the election in many different forms — from the seemingly academic to the most popular/populist, from op-eds (opinion-editorials) to Tiktok. The common line goes this way: Marcos’ (and Duterte’s) win is the poor’s protest against the rule of the oligarchs of the Philippine society. In particular, it is a reaction to the Aquino’s post-EDSA failure to listen to the poor. The defeat means revolt against “the yellow and the pink.”

Rodrigo Duterte earlier benefitted from the binary discourse (oligarchs vs. the people) characteristic of all populist discourses against liberal democracy and liberal capitalism worldwide. This explains the success of other “populist” leaders worldwide — Bolsonaro of Brazil, Modi of India, Putin of Russia, and earlier, Trump of the US. Populism is the name of the game.

How do we understand such a charge?

On the one hand, the Philippines has always been a society ruled by the elite — from the time of the “illustrados” and “principalia” to post-War Philippines, there has always been 30 to 50 to 100 families that ruled Philippine economy and politics. Marcos, Aquino, Estrada, Arroyo, Duterte campaigned under the banner of dismantling this oligarchy but did not do so. Marcos instituted his own cronies; Aquino in the end capitulated to big business; Estrada and Arroyo were convicted of plunder and named as the new oligarchs of our time. For all his bravado, Duterte ended by enriching himself and his group of the new Davao and Chinese elite, aside from killing thousands of poor people.

Duterte is right. The reign of the elite is the fundamental problem, the original sin, as it were, of Philippine politics. But blaming it entirely on the “dilawan” (or pinklawan as Isko Moreno did) is a constructed, selected and myopic view that forgets the whole historical baggage of elite rule in Philippine society.

And the spread of these lies and hate against one sector or some personalities, the selective enthronement of a “golden past” and deletion of atrocities during that past is made possible by social media networks (Facebook, Tiktok, YouTube), the great money poured into them over a decade or so, and the thousands of paid trolls to spread such lies and disinformation.

Our local group in this rural town identifies “fake news” as the main engine of the Leni-Kiko defeat. People in far-flung areas which has access to internet parrot spliced slogans from Tiktok: “Leni lugaw,” “luting,” “bobo,” “mahina dahil babae,” “puppet ng mga dilawan,” etc. Even as this group tries to explain, some BBM supporters close-mindedly shout and jeer at them. But Bongbong Marcos has already admitted: “My troll army won the Philippine presidency for me.”

Blaming it entirely on the oligarchs/elite also erases the reality that ordinary people—and there are many of them — do not sell their votes, stand up to local political warlords and economic elites despite the temptation. This simple ordinary people have held the moral line, as it were. Our little group finds it a joy to be welcomed, with snacks and smiles, by these people who do not believe in such lies.

- ‘MORAL POLITICS’ PERSPECTIVE

This view thinks that the political arena is a fight between good and evil. Marcos Senior and Junior as well as the Duterte’s are sometimes portrayed by their enemies as personifications of “evil.”

On the one hand, the Christian faith consider some moral values are non-negotiable (e.g., right to life, human rights, value of truth). Not to defend these values would mean agreeing to forces of evil. One writer calls this “moral politics.” On the other hand, like the structural binaries of elite and the massed, the discourse of good and evil makes us look down and “demonize” others who do not uphold our values, who do not think the way we do, who are ”lower” than us, who do not understand enough. This is seen in the “bobotante” and “tanga” charges against Marcos-Duterte supporters. But the same is true with the BBM-Duterte trolls against Leni as “lugaw” and “bobo.”

On the one hand, to deny that “morality” has no place in the political world is to give way to transactional politics, that is, any means is possible as long as it achieves the political end to win. To give way to “Machiavellianism” and justify it as social ideal spells a dead-end for our society. Marcos and Duterte campaign is characterized by this discourse.

On the other hand, moral politics with its binary lens prevent us from truly understanding the actual issues on the ground: Why do people insist on voting someone who is “evil?” “Bakit ba gusto nila ang magnanakaw, mamamatay-tao, at sinungaling?” For many people in most vulnerable situation, to “vote wisely” as the PPCRV tells us, does not mean to follow idealistic criteria. It is to follow the benign patronage of the barangay chairman or the mayor who has the resources when they need them most (for instance, when they need the ambulance for a sick family member or the much needed “ayuda” in times of disaster). “Di bale na korap, basta madaling lapitan.” And whoever s/he endorses, we will obey.

The so-called political ideals and criteria for voting — Christian, civil society or otherwise — do not easily fit the difficult situations where the majority of our population are. Until the unequal structures of this society continue to exist, patronage politics will always hold sway. Callous politicians will always “use” the poor as they are doing today, and for moral-religious politics to condemn the “bobotante” is actually to blame the social victims.

Like the “dilawan discourse” (elite democracy), the good vs. evil discourse (moral politics) is also a “generalized selective construction” which hinders us from truly listening to the needs of people on the ground.

- VIEWS FROM THE GROUND

Beyond these structuralist views, there are other factors on the ground that can help us understand the situation. There are three more that I gathered from the experiences of this group: the force of political machinery; the realpolitik of money; and the reality of election fraud.

Not having political machinery on the ground that supports the Leni-Kiko campaign is already a minus factor. Even as there are resources from pink supporters and volunteers, it is nothing compared to the compulsive force of political structures on the ground. We can gather thousands in the rallies but, on the actual day of voting, their stream of watchers, the endless give-away from food to bus service to a promise of “swimming” after, are already a force to reckon with. “We had little time; it was too late to volunteer,” the group said. While on the Marcos-Sara side, a list has been going on and updated even before the election campaign. Some list of names where one belongs promises them a share of “Tallano gold” when Marcos takes power again or a forwarded cash on the ATM card given even long before.

The second factor that is officially unsayable in Philippine politics is “money.” Yet people on the ground know it and talk about it. Realpolitik in the Philippines presupposes money. While on house to house, some people bluntly and unabashedly ask for money: “Is there no envelope that goes with the sample ballot? How much are you giving?” “Magkano?” Before the campaign, in one Barangay, Leni was winning in the survey. After the counting, she was left far behind. In our little town, most if not all of the four parties gave money away (from 800 to 1,500 pesos per voter) and all of them supported BBM-Sara Team. Marcos and Duterte should win regardless of whom you choose among the local candidates.

In one barangay, a candidate resolved not to give money, he got only one vote! The process of vote-buying has already improved as compared to days of old: ATM cards to QR codes are given instead of actual cash. DSWD assistance for typhoon Odette victims was delayed for five months and released just on time of election. Most people do not really believe that our small group of volunteers went house to house under the noonday heat without compensation. That is still unthinkable in Philippine politics.

The third factor is election fraud. It is maybe impossible to prove this for now. But people on the ground think that something went wrong with the voting last May 9. Real questions remain in people’s minds: statistical impossibility of the election returns transmission and the unbelievable speed with which it came, the thousand voting machines that malfunctioned, the zero votes for Leni-Kiko in many places, irregularities in the COMELEC process which were protested upon but were left unheeded, etc. Regardless of how you hide it, these questions remain. Regardless of the seeming big number (31 million), this government will always have a questionable legitimacy. It would be quite expensive to defend its rule.

For a start, it needs 15,000 security personnel to guard its inauguration; or to create a new Vice Presidential Security Group to defend themselves from real or imagined threats to their power. This is just for a start.

- THE LONG REVOLUTION

In 1961, a British neo-Marxist whom I studied closely, Raymond Williams, once wrote a book “The Long Revolution.” He writes: “It seems to me that we are living through a long revolution… a difficult revolution to define and its uneven action over so long a period that it is almost impossible not to get lost in its exceptionally complicated process.”

People were optimistic of such a revolution in the 1960s: political and colonial dictatorships were crumbling; industrial and technological developments were on the rise. But Williams was quite prophetic: five decades after, this progress was put into question. Technologies ravage the environment; populist regimes are on the rise and cultural advance appears to have gone back to square one.

The same is true in the Philippines. Our gains in democratic space have been narrowed once more. The search for common truth is eclipsed by noisy paid trolls and historical deniers. Honesty, accountability, humanity, kindness — virtues we learned in the family — are frowned upon. In exchange, what society rewards are transaction, convenience, cynicism and deceit. Truly, a difficult and bleak long revolution!

The election losers are feeling low and depressed. Yet ironically the winners could not also fully celebrate.

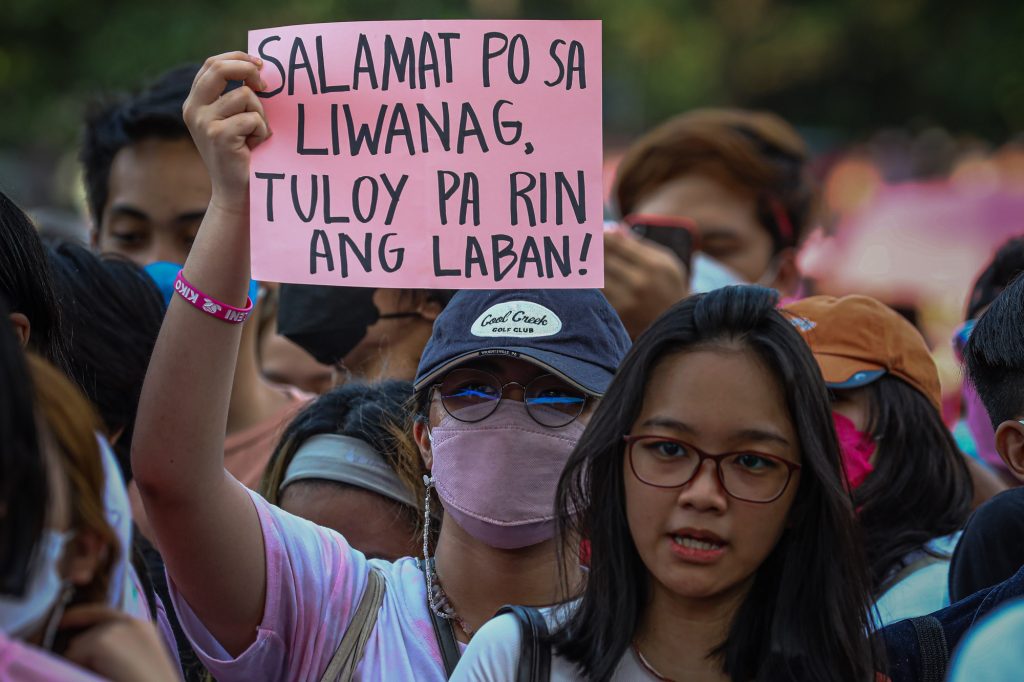

Our young volunteers and simple mothers did not deny the pain of loss. But when I asked them to describe their recent political experience, ironically, the images they gave me were metaphors of hope: a growing plant, deep roots, a book to fight fake news, a trophy of victory, a lighted torch (liwanag sa dilim).

In that reflection forum, they reminisced with joy their experiences during the house to house campaign: the wonder of meeting other young people with the same dreams; the fun of being offered food among poor families they did not know; the fulfillment of being able to defend a value in front of others who did not agree; the excitement of building friendships in new places. One of their greatest joys is to fight for the hope Leni and Kiko showed them. They requested me to say “hi” to VP Leni Gerona Robredo. I promised them to tag her.

“To be truly radical,” Williams also wrote somewhere, “is to make hope possible, rather than despair convincing.”

There are only few of them in my town. But there are 15 million of them all over. They resolve to continue to gather, to organize their group, to correct fake news, to build more friendships, to reach out and trust others, to stand up with pride despite the loss. They will demand public accountability and clean governance, to call out human rights abuse, to reject patronage politics.

Raymond Williams is realistic with the bleak political situation. But he is ever hopeful: “No mode of production and therefore no dominant social order and therefore no dominant culture ever in reality includes or exhausts all human practice, human energy and human intention.”

As I was listening to these young people, I can sense a new kind of politics — I still do not know how long — in the “long revolution.”

Father Daniel Franklin Pilario, C.M., is a theologian, professor, and pastor of an urban poor community in the outskirts of the Philippine capital. He is also Vincentian Chair for Social Justice at St. John’s University in New York. The opinions and views expressed in this article are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of LiCAS News or its publishers.