When we talk about the global policymaking processes for addressing the climate crisis, the annual Conference of Parties (COPs) often get the most attention. It is where countries formally agree to decisions that would shape how we limit global warming, adapt to numerous impacts, and reduce the vulnerabilities and risks that billions of people face.

Yet many of the details that form these decisions are actually decided between the COPs. This June, negotiators, experts, and other delegates will convene in Bonn, Germany for intersessional meetings to address issues that either were unresolved or lacked significant progress during the last COP held in Egypt last year.

As with every global conference, these intersessionals (SB58) are of tremendous significance for the Philippines, one of the nations at the highest risk of the climate crisis. The government has identified adaptation, climate finance, loss and damage (L&D), and the Global Stocktake (GST) as among its priority issues at SB58.

The Philippines must regard SB58 as an opportunity to build momentum toward decisions at the next COP that would accelerate global climate action.

On L&D

The agreement to establish a funding facility to address L&D is easily the most significant outcome of last year’s COP. It is a major win for the most vulnerable nations and communities, who have been calling for high-polluting nations to pay for causing the climate crisis and the impacts inflicted on them.

Now the challenge is to decide how this mechanism would be structured and operationalized. In Bonn, the Philippine negotiators must work together with other vulnerable countries to call for an L&D funding facility anchored on the “polluter pays” principle, referring to both developed countries and fossil fuel corporations. The funding should be given in the form of grants instead of loans, as it would be unjust to further burden developing countries that could limit their pursuit of sustainable development.

The Philippines must also call on said nations to commit to L&D finance as additional funding instead of simply realigning existing finance that is allotted for mitigation or adaptation. The amount allocated to the L&D funding facility should also increase at regular intervals, given the current scientific projections of likely increasing losses and damages due to worsening impacts.

On adaptation

When it comes to mitigation, the ultimate goal is to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, considered as a point that when exceeded would lead to potentially irreversible loss and damage. For adaptation, the corresponding goal is known as the global goal of adaptation (GGA).

However, the COP in Egypt failed to define what this goal would be or how it would be operationalized. At SB58, the Philippines should call for institutional arrangements, procedures, and activities aligned with the GGA being locally-driven, evidence-based, and gender-sensitive, given that climate change affects areas and stakeholders differently.

It is necessary for the GGA to account for the needs of the most vulnerable peoples (i.e., women, youth, indigenous peoples, and persons with disabilities), the risks they are facing, and their current capacities for adaptation. Similar to L&D, funding for adaptation and resilience-building solutions should be as directly accessible as possible, provided by funders such as developed nations, banks, and other private entities.

With other developing nations, the Philippines must also continue to pressure developed countries to follow through with their collective pledge to double adaptation finance. This would also address the issue of a global imbalance of funding that favors mitigation over adaptation.

On climate finance

Developed countries failed again to deliver on their promise to raise USD100 billion every year for developing nations to support their implementation of climate solutions. Largely due to this, world leaders are now discussing the establishment of a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) on climate finance that would sufficiently respond to the growing needs of the most vulnerable.

The intersessionals would feature several events tackling the NCQG, on which the Philippines should make a strong statement. Its delegation should call for the said goal to be a matrix that recognizes mitigation, adaptation, and L&D as the pillars of climate action and finance. Financial flows must be more easily accessible for developing nations like the Philippines, learning from the challenges experienced globally and domestically.

It may also call for framing the NCQG as an enabler of achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Doing so increases the likelihood of greater and accelerated mobilization of climate finance, especially from those within the private sector.

On GST

The GST is the assessment of the overall progress of global climate action, intended to generate outcomes that would form the basis of higher targets and scaled-up solutions. While it will conclude at the next COP in Dubai, SB58 would mark the end of the stages of information collection and preparation and technical assessment.

Among the key issues that must be tackled under this theme include national greenhouse gas inventories, implementation of Nationally Determined Contributions, state of adaptation initiatives and financial flows, and addressing L&D. The intersessionals should ensure that the data assessment is done towards identifying concrete solutions and well-defined pathways that are 1.5°C-compatible.

Even if significant progress would be achieved at SB58, without a strong commitment to ending the era of fossil fuels, the benefits of adaptation, avoiding L&D, or any other workstream would be neutralized. This is something that the Philippines and every other country must not ignore, in words and actions.

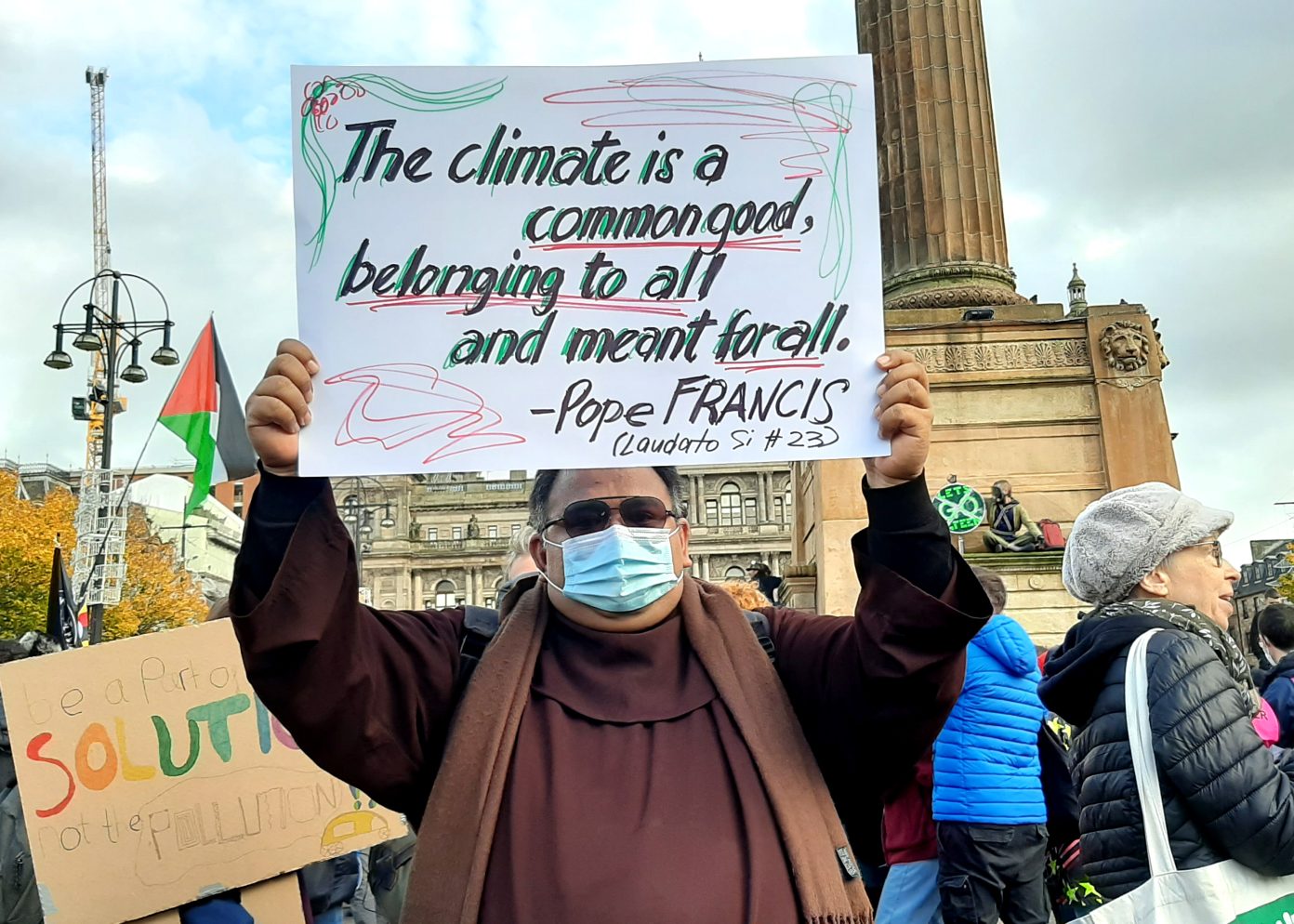

John Leo is the Deputy Executive Director for Programs and Campaigns of Living Laudato Si’ Philippines and a member of Aksyon Klima Pilipinas and the Youth Advisory Group for Environmental and Climate Justice under the UNDP in Asia and the Pacific. He is a climate and environment journalist since 2016.