Thailand’s decision to hold talks with Myanmar’s military has again tested the unity of Southeast Asia’s main regional bloc, analysts said, questioning why the Thai government called the meeting, especially after being trounced in last month’s election.

Key member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations that have criticized the Burmese junta – Malaysia, Singapore, and current ASEAN chair Indonesia – snubbed the gathering, which Bangkok defended on Tuesday by saying it was held in Thailand’s best interests.

Thailand and Myanmar, along with five other ASEAN countries – Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and the Philippines – as well as India and China, attended the meeting in Pattaya on Monday, Thai Foreign Minister Don Pramudwinai said in a statement afterward.

Those officials who attended it included a mix of foreign ministers, envoys, and representatives.

Cambodia and the Philippines, though, “signaled their discomfort” by not sending their top diplomats, according to Hunter S. Marston, a researcher on Asian affairs at the Australian National University.

“[Thailand] is actively undermining ASEAN centrality by forcing extremely uncomfortable choices on member countries who would rather not be exposed to such scrutiny for willingness to engage the junta,” Marston told BenarNews about Thailand’s efforts to engage with Myanmar’s military regime.

The meeting “risk[s] a dangerous diversion of diplomatic resources and attention away from the office of the special envoy in Jakarta,” he added.

Thailand’s approach was also at odds with Indonesia’s “quiet and more inclusive” diplomacy, Marston said.

“Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia have taken a clear stance in opposition to the Thai approach,” he said.

Indonesia this year holds the rotating chairmanship of ASEAN. It has set up a special envoy’s office in Myanmar to deal with a crisis that erupted in that country after the military ousted an elected government on Feb. 1, 2021.

Jakarta has also quietly engaged with the Burmese parallel civilian government and military administration, as well as China, India, and Thailand, to solve Myanmar’s post-coup strife, Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi revealed in May.

In October 2021, ASEAN as a bloc decided to exclude any representative from the Myanmar junta from its meetings after the military regime reneged on a five-point consensus for peace it had agreed to at an emergency summit of Southeast Asian leaders in April 2021.

The United Nations and human rights groups say the Myanmar junta’s security forces have killed thousands of civilians and the post-coup strife has displaced an estimated 1.5 million people.

Still, Thailand said on Tuesday it hosted the talks to complement ASEAN efforts and to protect its 2,400-kilometer (1,491-mile) border with the conflict-wracked country.

“Our ASEAN friends live far away and don’t have a connected border, so they are following their theory and they don’t see daily problems,” Thai foreign minister Don said. Cross-border crime primarily affected Thai citizens and businesses, he noted.

Participants found the meeting useful and wanted Thailand to hold it again, he added.

But Ngurah Swajaya, the Indonesian foreign ministry’s special advisor for regional diplomacy, on Monday evening reiterated Jakarta’s commitment to dealing with the crisis through formal ASEAN mechanisms.

“If one country takes an initiative, that’s fine, that’s their right,” Ngurah said at a press conference.

“But if we talk about whether this is in the context of ASEAN, there are rules of the game, there is the five-point consensus, there are summit decisions, that’s what we have to pay attention to.”

This was not the first time Thailand had organized informal or “Track 1.5” dialogues with the Myanmar junta.

In March, Thailand convened a meeting among countries that share frontiers with Myanmar such as Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam, as well as Bangladesh, China, India and Japan to discuss border issues and approaches to the crisis. India hosted a similar round of alternative meetings a month later in New Delhi.

“There are ASEAN members that could identify with the military regime more than others,” said Joanne Lin, co-coordinator for the ASEAN Studies Centre at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

“ASEAN countries that are bordering Myanmar will have their separate concerns including movements of refugees, trafficking in persons, drug trafficking, and, therefore, they may feel the need to engage with the [Burmese junta] to address these issues in a practical way.”

‘Preserving power’

Meanwhile, some analysts and observers raised questions about Thailand’s current administration holding such a meeting when it lost its mandate with Thai voters in the May 14 general election.

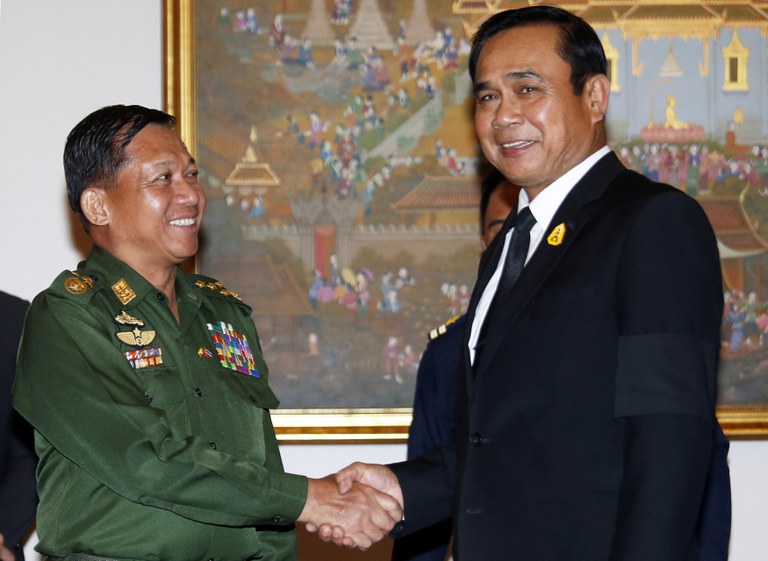

Analysts said the talks were likely an attempt by Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha’s caretaker government to maintain influence and close ties with the Myanmar military before a potential new government took office.

Foreign Minister Don said the decision to hold the meeting had already been in the works and the national polling body had only just (on Monday) certified the results of last month’s election. He did not see why Thailand’s interests needed to wait.

But the Move Forward Party, which won the most seats in Parliament’s lower house, on Tuesday, signaled its intention for a more active foreign policy, and a change in approach to Myanmar.

Party leader Pita Limjaroenrat reiterated his government’s “unwavering” commitment to ASEAN centrality on the issue of Myanmar.

“By prioritizing ASEAN centrality, promoting inclusive engagement, focusing on human security, and revamping our domestic approach, we aim to contribute to a stable and prosperous future for Thai and Myanmar people as well as the region as a whole,” Pita said in a statement.

Prayuth, a former army chief, became prime minister after leading a coup against the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra in May 2014. He stayed on in office following his election by lawmakers after the 2019 general election.

Salai Bawi, political scientist at Chiang Mai University, said it was clear the strategies of a potential Move Forward government would reset everything that Prayuth had established.

“Over the past nine years, the Thai military has formed significant relationships with the Myanmar military,” he told BenarNews.

“Therefore, preserving the power networks of the Thai military and the Myanmar government is crucial. … I believe this is an attempt by the [current] government to maintain its influential networks.”

A group of Southeast Asian lawmakers, meanwhile, called the Thai government’s move to hold the meeting with the Myanmar junta and others an “arrogant disregard for the unity of ASEAN, the human rights of the people of Myanmar, and even the will of its own citizens.”

The current Thai government was overwhelmingly defeated in the recent general election and no longer has a mandate from the people; initiating such talks in spite of this is a slap in the face of the Thai voters,” ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) Co-chair Charles Santiago said in a statement on Monday.