The staff of some hospitals in the Philippines have taken to wearing diapers to conserve dwindling stocks of physical protective equipment (PPE) amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Already battling great odds against a disease that has killed close to a thousand people, including several doctors and nurses, health workers also face severe mental health stress.

Rights advocates link these privations to flaws in the government’s emergency plans when it comes to a health crisis.

Foreign and local donations cannot keep pace with the need for protective equipment, which need to be discarded with every exit from COVID-19 wards.

“Remember, we work 12-hour shifts. How many times do we need to relieve ourselves over that time?” said Sean Herbert Velchez, head nurse at the National Orthopedic Hospital.

“To wear diapers at the prime of your life and relieve yourself that way strengthens the sense of self-pity and the perception that one has lost control,” said Velchez.

The fear health workers of getting infected by the new coronavirus disease ranks equal to the fear of infecting their families.

At least 1,300 Filipino health workers have been infected by the disease since March, more than 10 percent of the total cases, an attrition rate that ranks the highest among Asian countries.

“Many medical personnel didn’t have the proper training,” said Velchez during an online forum. “We didn’t just lack PPEs; we had substandard ones,” he said.

The PPEs are also very hot to wear. In some government hospitals, where cooling systems are poor and elevators are out of order, front-line staff carry patients up to three or four flights of stairs.

Summer in the Philippines comes with a heat index hitting between 42 and 50 degrees.

The combination of these factors erodes composure and can-do spirit honed by years of training to battle illness in a developing country.

In March, during the early days of community transmission, one nurse who came in close contact with a COVID-19 patient locked herself in an empty hospital room.

“She was there, not eating, not changing clothes, just weeping for two whole days until colleagues convinced her to come out for a test and more comfortable isolation quarters,” said Velchez.

“Some of us have set up tents on our lawns,” he added. Garages have become temporary bedrooms.

Others bear the long separation from children or parents. The burden is heavier on government health workers, many of whom live in areas under hard lockdown due to rising COVID-19 cases.

Safe havens

The Department of Health has ordered PPEs through the normal bureaucratic warren of rules, leaving it scrambling for supplies as the pandemic hit nations across the globe.

By April 15, only two tranches of a million PPEs had arrived in the country with 1,233 hospitals, not counting dozens of quarantine facilities for suspected COVID-19 cases.

The government is also catching up with the backlog in testing, which has contributed to communities’ irrational behavior toward health workers.

Landlords and neighbors have driven away hospital workers from boarding homes, condominiums, and other residential areas. Some have landed in hospitals from physical attacks.

“We are housing more than 800 front-liners in more than 25 institutions, including schools, parishes and hostels,” said Bishop Broderick Pabillo, administrator of the Archdiocese of Manila.

These are also safe havens for those who want to spare families the risk of contamination. The church also provides for the food.

Ten of millions of poor Filipinos bear the brunt of mental stress due to livelihood and jobs loss amid a lockdown on its second month.

But the feeling of losing control over life also affects the middle and upper classes, said Dr. Noel Reyes, chief of medical and professional services at the National Center for Mental Health.

Those on the health frontlines need help to cope with the disconnect they feel in their wards and isolation centers. News coverage and the country’s social media users send viral paeans of gratitude. On the ground, they face fear and loathing.

The country’s premier psychiatric institution has dedicated hotlines for health workers and more for the general public. At least half a dozen private institutions have also set up help centers.

“A listening ear is a very important tool,” said Reyes.

“One may just need someone to talk to about their aches, worries or anxieties, and this is as valuable as a real consultation,” he said.

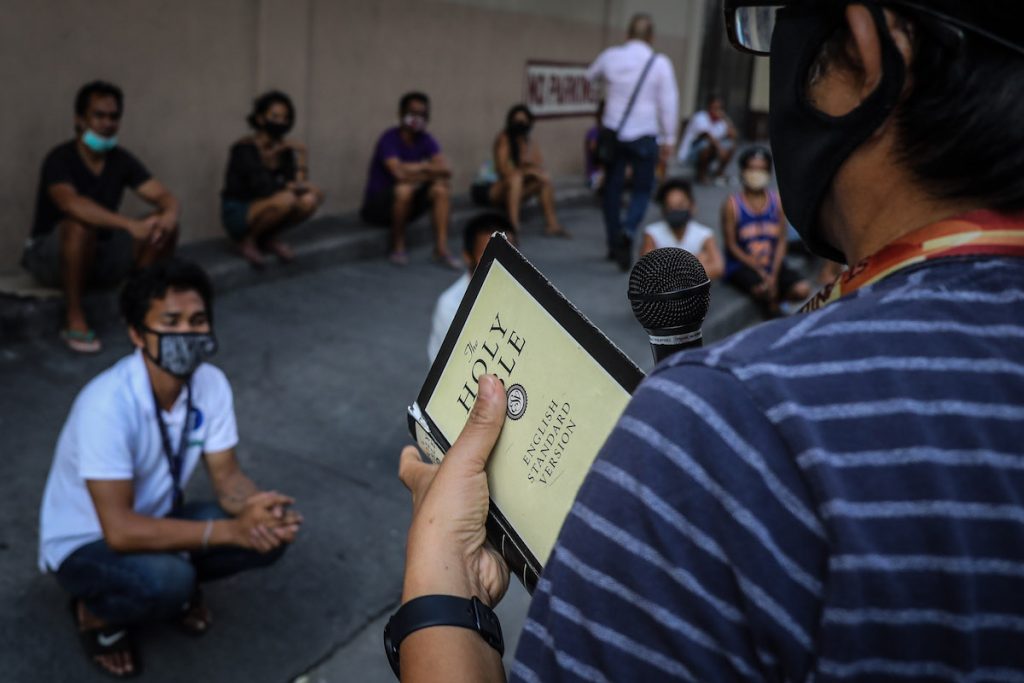

Carmelite priest Gilbert Billena oversees regularly dialogues on human rights with enforcers of the local quarantine unit in the community in his parish.

The enforcers are torn between fear of being accused of neglect and compassion for fellow citizens, said the priest.

Few have PPEs aside from masks, some of these hand-made by their families. They receive allowances lower than the minimum wage and are as poor as their neighbors. They patrol under the withering summer heat, a grave health danger.

Father Billena conducts online Masses like most priests in the country. Religious activities, considered mass gatherings, have been stopped since the government imposed a lockdown.

There are guidelines. And there are judgment calls.

When representatives of a very poor area, where residents could not afford internet or even power connection, appealed to hear Mass, Father Billena would visit, conducting the service via a public address system.

“I distributed the consecrated host to the families who participated. We also practiced social distancing, but the effect was dramatic,” he said.

The parish and the village head started stress debriefing in April for frontliners, including members of local government health emergency response team.

It took place in the church, with the parish providing digital access to the National Association for Social Work.

“Every participant has an assigned Registered Social Worker and the stress debriefing is done through cellphone,” said Father Billena.

Even the ‘haves’ struggle

Reyes isn’t exaggerating when he notes that mental stress affects all classes during the pandemic.

Peachy Rallonza Bretaña, an advertising creative executive and wife of a lawyer, said coping with bipolar disorder is a challenge even with a career on full-blast or when she was being hailed as the person who sparked a “Million People March” against corruption in 2013.

The pandemic froze all projects and the income it brought her and kept the family inside their townhouse.

“We’re two bipolar in the household and being together 24/7 is quite challenging because we can’t take breaks from each other,” she told LiCAS.news in an interview.

“We can’t really ‘leave’ to cool down. It’s suffocating, it’s depressing,” she said.

It doesn’t help that therapy sessions have been put on hold. Online consultations don’t have the same effect as face to face interaction because of subtle shifts in behavior.

There’s also the inhibition that comes from knowing that many social media applications carry grave risks to privacy, an issue that hounds people with mental illness even in the best of times.

“Losing sleep, not sleeping on time, waking up later, bingeing on shows, unhealthy food — I’m guilty and it contributes to an unhealthy state of mind,” said Bretaña.

She knows the danger signs: passive suicidal thoughts, the feeling of detachment, not wanting to do much, loss of sleep, too much sleep.

“Knowing all these but being numb to do anything about it” is a great struggle.

Her son has joined an online penpal group, something novel to the text and meme generation. Letter writing helps him cope because it needs more deliberate thinking.

“I can see that it gives a semblance of normalcy. It helps him focus on something that brings him joy at least,” she said.

“The young ones need their friends. Their friends help a lot in lifting their spirits, especially those with mental health issues,” Bretaña added.

News as a trigger

Belle Mapa, a freelance writer and journal artist and mental health advocate, was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder in 2017, but has struggled with mental illness since 2014.

“Before all of this, I had a working routine. Now, I’m fighting insomnia, the days blend together because my environment doesn’t change,” she told LiCAS.news.

“The news keeps me up, and I’m alone with my feelings in the silent hours,” she said.

Mapa’s triggers are violence and anger in the news.

Information overload and knowing that events are out of her control is a major stress point, said the former lifestyle journalist.

“There’s a lot of anxiety and anger because we’re so hyper-aware of what our leaders are and aren’t doing. Not to mention fear,” she said.

She said her “lowest points” during the quarantine were when President Rodrigo Duterte ordered the police to “shoot dead” lockdown violators and the shooting of a former army man with mental issues.

The health department estimates that about 22 million of the 110 million people in the country suffer from mental, neurological, or substance abuse disorder.

About 14 percent of people with physical disabilities also suffer depression, said Reyes.

Triggers vary from person to person.

“For others, it could be providing for their families, or thinking of supplies, or having to psych themselves up to go outside for a grocery run,” said Mapa.

“That a lot of things right now are ambiguous and unknown doesn’t help people like me who are prone to depression and overthinking,” she said.

Psychology student Alyssa Lopez is not considered a mental health patient, but she talks about “a sense of dread looming over me even if I’m safe at home.”

Like Mapa, Lopez gets affected by news of conflicts “and constantly being bombarded by numbers in the media.”

Seeing people make unwise decisions like breaching quarantine also frustrates her. Yet Lopez said on one level she understands the desperation.

“During this pandemic, I’ve also started to realize how privileged I was that my family could still earn and be able to put food on the table even if they were working at home,” she said.

That reflection, however, comes with a downside.

“Guilt also surfaces because I can’t really do anything to help others who are struggling,” she said.

Seeking balance

Vivian Go works as a counselor for Catholic families in crisis. Like other church institutions, the center where she works in her parish remains closed.

“The Philippines may not be the worst hit in terms of victims and death in the whole world, but economic stability has taken a bad hit,” she said.

“So many people are jobless, small businesses are closing because they can’t sustain the long-term lockdown,” noted Go.

She said the marginalized sector are the most devastated. “Hunger and zero income would result in crime,” which in turn raises fear among other social classes.

“The lockdown on families has brought about anxieties due to fear, worries, tension, paranoia, and some just feeling lost,” she said.

“The uncertainty of the situation pulls down the energy of the family. Reversal of finances brings stress to everyone,” added Go.

She used Mapa’s term, “in limbo,” when referring to young Filipinos. She also echoed Dr. Reyes and nurse Velchez’s observations about people feeling the loss of control.

When young people suddenly find their personal map blurred, it can cause dislocation in the psyche, although mental issues arise in the young and old alike.

When friends and clients call, Go tries to gently turn them away “from the gruesome situation with which we are not in control of” and focus on something they can actually manage.

Practical health tips help, like how to boost one’s immune system and proper hygiene. Apathy toward these is a warning signal that greater intervention by medical professionals is needed.

But Go also sees many families becoming closer during the pandemic.

“They become more prayerful, more discerning in terms of expenses and budgeting. Some families become more resilient,” she said.

But many have also questioned the presence of God, the counselor acknowledged.

“I think, this is the time when the Church has to reach out to their parishioners who are going through hunger, sufferings, and sickness, by making them feel their presence and availability,” Go said.

Online Masses for Catholics, worship services for Christian groups, and other spiritual activities can help. Go advised clergy to answer calls or text messages when parishioners seek help.

A voice joining in prayer over a social media app or even over the phone can be a powerful balm to the spirit, she said, calling it a version of an embrace, a hug, a guiding hand.

Father Billena agrees. If there is anything the pandemic taught the Carmelite priest, it is humility.

“Even when you don’t have the answer, be there,” he said. “Knowing that they are not the only ones feeling confused is a gift.”

This is article is the third of three parts.

First part: Churches in Philippines struggle to help those battered by pandemic

Second part: Philippine church people walk with poor amid threats, challenges