Rising mental stress amid the Philippines’ almost two-month lockdown has sent Catholic clergy brainstorming how “to be as close as possible to the flock at a time of hunger, death, and loneliness.”

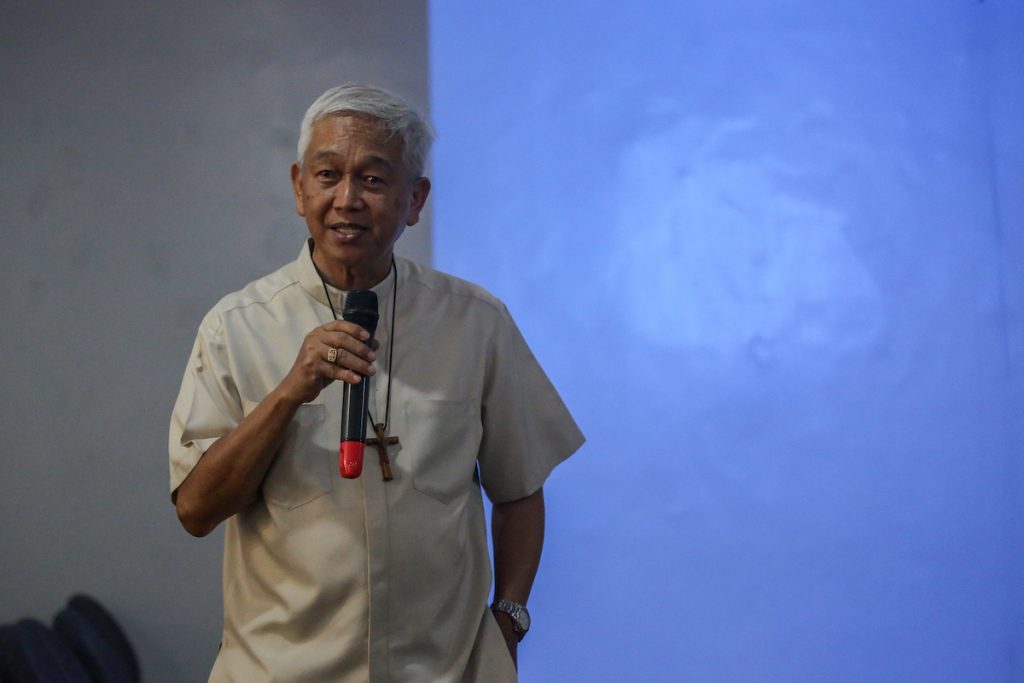

“Online ministry is not enough,” Bishop Broderick Pabillo, apostolic administrator of the Archdiocese of Manila, told LiCAS.news in an interview.

Amid rising distress calls to mental health hotlines, the country’s Catholic bishops have crafted protocols aimed at convincing the government to relax rules on the holding of religious activities.

“We will try our best to control those who come (for the religious activities),” said Bishop Pabillo. “We are coming with our protocols to avoid contamination,” he said.

But priests and church workers who scour Manila’s slums and the hidden nooks that hide the homeless to bring food and other basic needs say that expressions of solidarity are as important as religious rites.

The government plans to ease quarantine rules by May 16, exactly two months since the start of what President Rodrigo Duterte calls “a lockdown.” This would mean limited resumption of work and business activities in some provinces.

However, the interagency task force handling the government’s response to the pandemic took back an early announcement on allowing religious services — lumped under “mass gatherings” — for fear of sparking a new round of coronavirus cases.

Officials credit the “enhance community quarantine” for managing the spread of the disease in the country.

But the loss of jobs and livelihood for at least 18 million Filipinos has triggered a fight or flight response among poor families now baking inside hovels, many without water and with little ventilation as the heat index hits above 42 degrees.

Poor left out in the cold in Philippines’ race to stem coronavirus spread

“While only a few — considering that we are more than 100 million — have been affected by the disease, all families have been economically hit by the lockdown,” noted Bishop Pabillo.

“For the poor who depend on daily earnings to survive, this is a very big challenge,” he said.

“People do not only need physical health,” said the bishop. “Their mental and psychological health need to be promoted, and religious activities help a lot,” he added.

Father Danny Pilario, a Vincentian missionary who ministers to a sprawling slum in the outskirts of Manila, has a slightly different perspective on the flock’s need for formal faith structures.

“In the context (of the pandemic), their homes have become their church, the parents have become spiritual leaders of their families,” he said in an interview with LiCAS.news.

“If we think about it, not everyone goes to church regularly, even without [the new coronavirus disease]. Maybe once or twice in a year for many people,” he said.

“And they keep on with their faith with or without the priest. So, they will survive,” added the priest.

Father Pilario, however, said church workers need to go near to the desperate, scared, lonely and grief-stricken flock.

“Maybe, physical nearness is needed so that people will know that the Church is there in these most difficult times of their lives,” added the priest.

Stigma and contempt

The National Center for Mental Health has seen between 50 percent to 75 percent increase in the number of distress calls since the start of the lockdown.

Dr. Noel Reyes, the center’s chief of medical and professional services, said calls pertaining to anxiety are more common than suicide.

“The current situation with COVID-19 appears to have caught everyone by surprise. Most of us are unprepared,” he told LiCAS.news.

The Department of Health estimates that 22 million Filipinos suffer from mental, neurological, and substance-abuse disorders.

The official registry of people with disabilities, however, only lists 14 million, with 14 percent suffering from mental and neurological problems.

The list includes 600,000 Filipinos with epilepsy and people suffering from dementia, which affects five percent of the country’s elderly.

“Stigma remains a primary barrier for one to seek help from a mental health professional,” said Reyes.

He said people from “low socio-economic groups” are at “high risk” for mental distress, especially during times of crises.

But mental illness does not spare those from the high- or middle-income families, he said.

There is no single trigger for depression and anxiety, nor is there any balm that fits all.

The upending of work and social patterns has sparked a mental health crisis in a country that lags badly in health care metrics.

Citizens, health providers, and spiritual shepherds find themselves in a struggle against a second “invisible enemy” as the primary invisible scourge continues to rampage.

A common plaint among people suffering from mental strain, even those from the middle and upper classes, is the feeling that they have lost control over life.

Like thousands of medical personnel across the country, Father Pilario, Father Gilbert Billena of San Isidro Labrador parish in Quezon City, and an army of church workers risk their lives daily to help people survive the contagion and the lockdown.

They warned that uneven and inadequate social welfare aid, and the inability to find survival mechanisms, have turned slums into tinderboxes.

Anxiety and anger levels spiked as the last day of distribution of government cash aid on May 10 caused pandemonium among residents of urban poor communities.

Thousands of people, including the elderly and people with disabilities, squirmed against each other on the streets, pressed against gates of schools, screaming, weeping, desperation trumping all regulations on physical distancing.

It was a scene recorded across the country.

“Some are told they are unqualified when they reach the end of the line; some already suffered from heat stroke and heart attack. Is there no better way?” said Father Pilario.

“This incompetence is killing the poor,” he said.

The money, about US$160, isn’t even what a minimum wage earner gets in a month in Manila. Millions, on the other hand, have received nothing from the Social Welfare department.

Government critics blame a convoluted vetting process.

Bishop Pablo Virgilio David of Kalookan noted a “dysfunctional society” where those most in need are unregistered and unrecognized by the government.

Losing control over life

Anger is a normal part of facing crises, according to Dr. Reggie Pamugas, mental health expert of the Community Medicine and Development Foundation.

“It is the sustained feeling of losing control over life, when you feel the world is no longer a safe place,” that can trigger depression, he said over a digital health forum dubbed Second Opinion.

Father Pilario has spent the last eight weeks scouring areas where homeless people stay to bring hot meals.

The poor have no problem with generosity, he said. They will divide the little they have with kin and neighbors.

“It is disorganization, government neglect that is the chief problem,” he said of the cash aid distribution chaos.

The homeless have become great teachers and source of inspiration to the priest. But there are times when he, too, despairs.

In a poignant homily about good and bad shepherds, the dean of his congregation’s theology school in Manila bared that pain.

He described the desolation in what was once a metropolis that hardly slept with empty roads that are now silenced except for the sound of sirens of ambulances.

Father Pilario knows it is not the silence of rest nor satiety.

He tried to imagine those who cannot sleep because of hunger.

“I feel helpless, empty and in pain. Then I begin to ask where might God be,” he confessed.

“When Jesus the Good Shepherd sees all these, his heart goes out to them, I know, but where is he? He sends us shepherds today but where are they?”

The country’s president, called “Father” by devoted followers, has framed his response against the novel coronavirus as a new “war.”

While not as bloody as his pogrom against drug users and dealers, the quarantine has led to a few killings and arrests of more than 150,000 mostly poor citizens.

The president and retired generals now holding top civilian posts in the Cabinet have ignored appeals for a more rights-based framework.

Brutal sanctions against quarantine violators, combined with a 24/7 news cycle and social media virality, have worsened mental health problems in a country where one in every five adults suffers from a form of mental or neurological disorder.