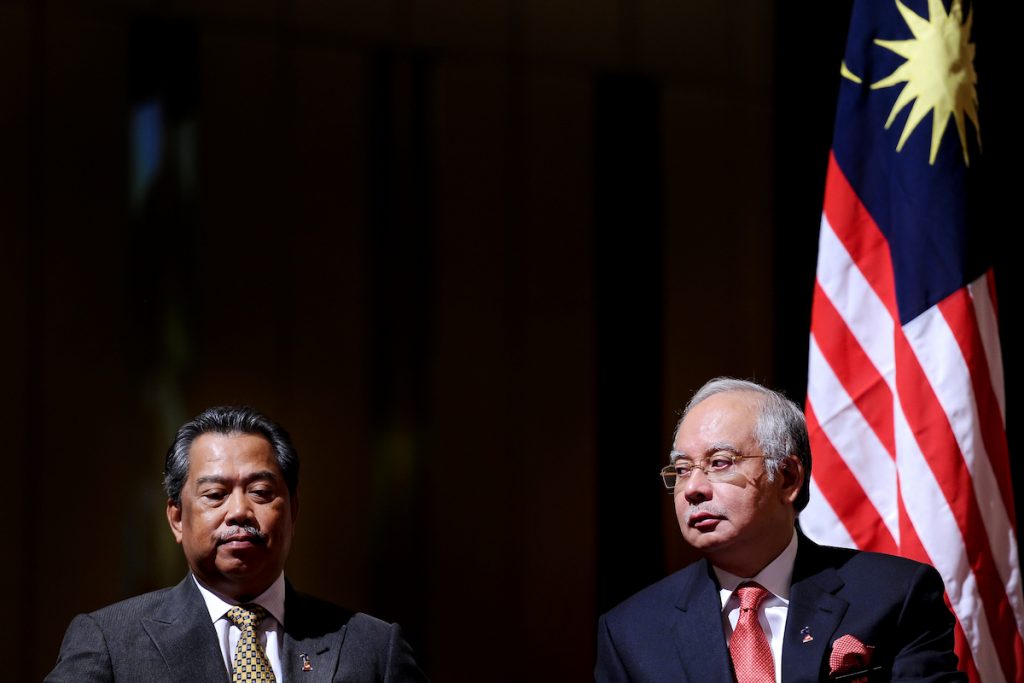

While state news service Bernama works hard to extol the virtues of Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin’s tenure at the helm of Malaysia, international and independent media outlets find themselves facing a series of punitive measures for anything the government sees as critical of its hold on power.

This is not new. If we look back to 2016, former prime minister Najib Razak was grappling with the Pandora’s Box that was the 1MDB scandal — his involvement in which would ultimately lead to his downfall — and to do so he needed to stifle domestic media coverage.

He infamously suspended, or simply closed down, any publications that reported on the issue. This was on top of running battles with news portal Malaysiakini and network Al Jazeera over a number of scandals that had followed him through his political career.

He was equally ruthless in quelling dissent among his own ranks, firing Muhyiddin who, as then deputy prime minister, casually quipped at a public event that he received his updates on 1MDB from one of the suspended newspapers.

So, four years later and knowing how Najib’s attempts to strangle press coverage backfired so spectacularly with his ousting from office in 2018, it seems oddly ironic that Muhyiddin would resort to similar tactics.

Yet, here we are, a little more than four months into Muhyiddin’s administration and attacks on the press have stepped up in ferocity, as outlets continue to report news that does not reflect well on his government. Or, as in one case, a member of the ruling coalition taking umbrage over a book of essays published about the 2018 general election.

To date, there are three overarching issues: Coverage of the government rounding up undocumented migrants during a lockdown; general criticism of perceived cronyism within the new administration; and threats to stifle opposition.

In the first instance, as previously discussed, South China Morning Post reporter Tashy Sukumaran is facing criminal charges for her coverage of Immigration Department raids on undocumented migrants in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor during a nationwide coronavirus lockdown.

In the past week, the Al Jazeera team that produces the documentary program ‘101 East’ has similarly been targeted by police for its coverage of the raids.

Meanwhile, Steven Gan, editor-in-chief of Malaysiakini, the nation’s leading independent news portal, has found himself caught up in a legal whirlwind for contempt of court after publishing a story on senior politician, Musa Aman, who has solid links to the Cabinet.

Musa was a former chief minister of Sabah, who fled the country after the general election in 2018 amid US$100 million corruption, bribery and money laundering allegations. He was arrested upon his return six months later and charged with more than 60 related offences.

Recently, Malaysiakini reported all charges had been suddenly dropped and readers were outraged, making their displeasure known in the comments section of the article.

The government decided the portal was in contempt of court because some of the comments trampled on the integrity of the judiciary, not least the chief justice.

With lightning speed, Gan has found himself in the dock, busy trying to defend himself against what he states as a simple oversight (in Malaysia, editors of online portals have a legal duty of care to moderate and remove any comment within a “reasonable” period of time that could be deemed insulting or derogatory about the government or the sultans).

Gan filed an appeal against the charges — maintaining they were grossly disproportionate to the perceived offence — which was bumped straight to the Federal Court, the highest court in the land, circumventing the High Court and the Appeals Court.

This gave Gan no grounds to appeal a filing he subsequently lost. Thus, he will stand trial for contempt of court and faces 12 months in prison, if found guilty.

Gan has received widespread support from his contemporaries in the media, while members of the Malaysian Bar have commented with some alarm at the government’s steamrollering of legal procedure and precedent to have Gan stand before a judge.

Meanwhile, independent book publisher Gerakbudaya finds itself in similarly hot water for its latest release, Rebirth: Reformasi, Resistance and a New Hope in Malaysia.

An activist from the ruling coalition Umno party became incandescent with rage when he saw the cover, on which is a satirical depiction of the royal seal, claiming the country and the king were being pilloried for the whole world to see.

Ministers jumped on the bandwagon and instructed the police to throw the book at the publisher, Chong Ton Sin, who found himself at the fat end of the thin blue line as officers stormed into his office, seizing equipment and books, and detaining him.

Chong has — under duress or a desire to stave off the possibility of serious jail time — apologised unreservedly but the police, backed by snarling government MPs baying for dissenters’ blood, are in no mood for repentance.

Again, senior members of the legal fraternity are dumbstruck at such heavy-handed tactics. They quickly pointed out to the police that the contents of the book and the offending image did not belong to Gerakbudaya.

They argued that the essays and the image have been in the public domain and well publicised for a number of years — since Najib’s time, in fact — without even a hint of discontent at any time by anyone, so why now all of a sudden?

In short, they said there was absolutely no case to answer and this was little more than an attempt to silence opposition.

Moreover, there is deep concern from society at large about how quickly the police jump when someone from Umno spits out his pacifier and chucks all his toys out of the pram, reprising a years-old notion that the police are little more than uniformed Umno enforcers.

It should also be noted that the police are now abandoning tamer laws on public nuisance and annoyance when dealing with criticism of the administration, and are now quoting the Sedition Act — which carries much heavier penalties — to stamp their authority.

Observers have quite rightly pointed out there is a political backdrop to this move to crush free speech. Muhyiddin is treading water, clinging to his post by his fingertips, while all around him sharks swim in ever decreasing circles, taking bites out of his leadership.

Even though Muhyiddin is prime minister, his Bersatu party is the second largest next Malay nationalist party Umno in the ruling coalition.

Umno does not like playing second fiddle to anyone — let alone Bersatu, which splintered from Umno in 2016 — especially when Umno believes government belongs to it by right, having ruled from uninterrupted from 1957 to 2018.

Meanwhile, the opposition is in disarray, with leader Anwar Ibrahim casting off his liberal reformist image as, with Stalin-esque aplomb, he purges his party of anyone who does not declare absolute loyalty to him.

Nevertheless, it is the media and, by extension, the people who have to suffer the consequences of yet another political power struggle and desperate attempts to control the narrative.

Unlike democracies — where politicians feed the press with leaked stories of opponents or rivals — in this part of the world the media are hounded, sued or prosecuted into oblivion for any perceived slight, regardless of intent.

With that in mind, Muhyiddin’s crackdown is just the beginning of another dark chapter in Malaysian history, with no solution in sight and freedom of expression guaranteed only for the elite few with the right connections.

Gareth Corsi is a freelance journalist based in Malaysia. The views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of LiCAS.news.