Clive Hamilton and Mareike Ohlberg’s latest book, “Hidden Hand: Exposing How the Chinese Communist Party is Reshaping the World” is a tour de force of global Chinese influence, and a stake through the heart of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) attempts to covertly use its significant economic and diplomatic power to extend its global reach.

The book expertly exposes how China influences international politics in undemocratic and non-transparent ways, including through elite capture, academic influence, and purchasing strategic industries globally.

A motherlode of detail is included that deserves a very careful read — or two. Buried on page 143, for example, is a Chinese military intelligence organization, 2PLA, that has up to 50,000 “plants in organizations around the world, whose aim is to collect information, confidential and otherwise, to be sent back to China.”

Own goal by the 48 Group Club

One Beijing-linked association in London discussed unflatteringly in the book, the 48 Group Club, promotes trade and networking with Chinese elites. The group is named after a delegation of 48 “ice-breakers” who visited China in 1954.

On June 23 this year, the group’s lawyers launched legal demands against the “Hidden Hand” publisher and alleged defamation. But the book is meticulously well-referenced, and only one minor change to the text is apparently justified. That change makes the leader of the 48 Group Club, Stephen Perry, look even more compromised. Future editions of the book will be corrected to reflect that China Daily quoted Perry in 2010 as saying that while studying law in London, “I read about Marxism, Leninism and Mao Zedong thoughts more than law books”.

The authors summarize the history of the 48 Group as, “at the instigation of a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo, Zhou Enlai, the 48 Group was the work of three secret members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. From this foundation the club quickly developed an unrivalled level of trust and intimacy with the top leadership of the CCP, and has built itself into the most powerful instrument of Beijing’s influence and intelligence gathering in the United Kingdom. Reaching into the highest ranks of Britain’s political, business, media and university elites, the club plays a decisive role in shaping British attitudes to China.”

According to Hamilton: “The publisher in Britain is undeterred by the legal threat and has brought publication forward to 16th July.” The book is already available in Australia and will be released in the U.S. within weeks. The president of Optimum Publishing International, Dean Baxendale, is publishing the book in Canada. He said the book was available in Canada starting July 3.

Hamilton and Ohlberg are not the only authors to have come under attack for their research into Chinese influence. Others include Anne-Marie Brady in New Zealand, Valerie Niquet in France, J. Michael Cole in Taiwan, and Jon Garnaut and Drew Pavlou in Australia. Pavlou is an undergraduate and elected student leader facing dismissal for his activism and writing that criticizes China’s human rights abuse and Beijing’s financial links to his own University of Queensland.

China’s ambitions and influence

Hamilton and Ohlberg start “Hidden Hand” with an overview of CCP ambitions, including the transformation of the international order to fit its own image through influence and “without a shot being fired.” But influence goes both ways. The authors quote a 2006 Central Propaganda Department manual that states, “when hostile forces want to bring disarray to a society and overthrow a political regime, they always start by opening a hole to creep through in the ideological field and by confusing people’s thought.” Even Harvard professor Joseph Nye, who some would argue is soft on China today, was seen in 1990 as a soft power threat by Party leaders due to his advocacy of influencing China.

Taking Nye to heart, the CCP itself sought to export its own form of authoritarianism through the tools of soft power, based on the legitimacy of supposedly high GDP growth and a well-ordered (some would say too-ordered) society.

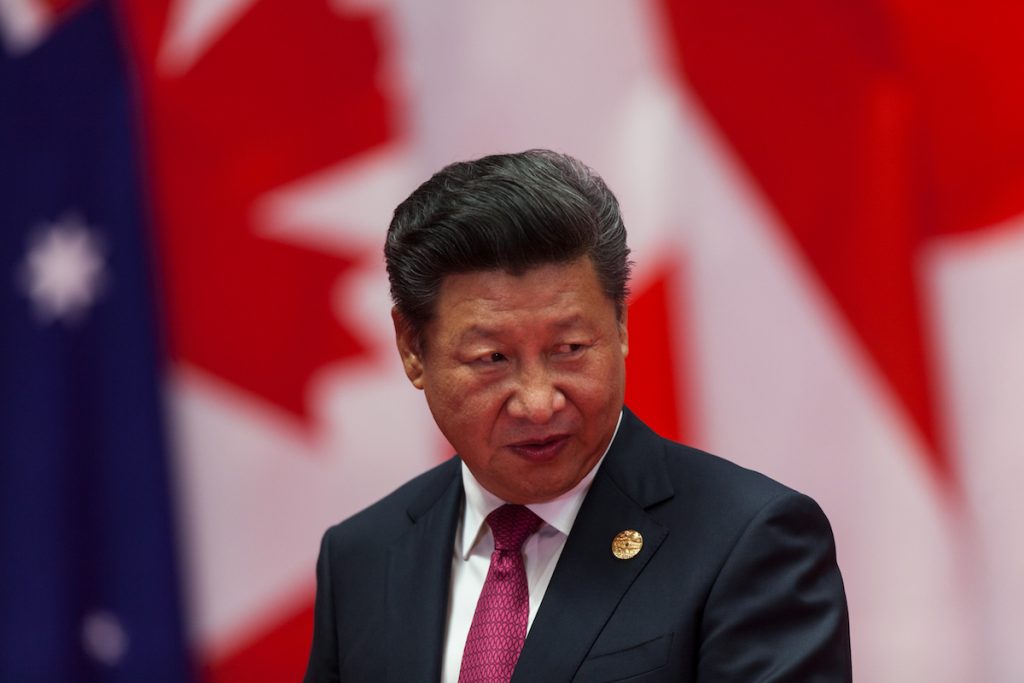

The authors note that the current CCP is a Leninist party dependent on communist ideology. General Secretary Xi Jinping said in a January 2013 speech, for example, that despite the Chinese system eventually triumphing over capitalism, cadres must be prepared for “long term cooperation and struggle between the two systems.”

He warned that one reason for the USSR’s collapse was that “they had completely negated the history of the Soviet Union and the history of the CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union]; they negated Lenin and negated Stalin; they engaged in ‘historical nihilism’ and brought chaos to their ideology.”

Naming names

An entire chapter of the book is devoted to Chinese influence on political elites in the United States, including those in business, academia, politics, think tanks, cultural institutions, and media. Targets are not only national, but at state and municipal levels as well.

Hamilton and Ohlberg take the necessary risk of naming names of those individuals and organizations on whom they have found evidence of participating, knowingly or unknowingly, in China’s influence operations.

The authors argue that U.S. business pressures Donald Trump to end the trade war, for example. They note that whenever China’s top trade negotiator, Liu He, traveled to the U.S. to meet with the Trump administration, he first met with Wall Street’s top bankers. Australian and Taiwanese businesses dependent on China also seek to affect their governments in what the Party calls “using business to pressure government” (以 商 逼 政).

The authors mention former Presidents Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush, Secretary Henry Kissinger, Secretary Hillary Clinton, Secretary Hank Paulson, Secretary Elaine Chao, Secretary Wilbur Ross, Senator Mitch McConnell, and Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner in the context of Chinese influence operations. Heads of state are implicated, including Britain’s Tony Blair, David Cameron and Boris Johnson, Canada’s Justin Trudeau, and Australia’s Kevin Rudd.

“When Deng [Xiaoping] called me a ‘lao pengyou’, an old friend of China, I felt the phrase was not just the usual flattery, but a recognition that I understood the importance of the US-China relationship and the need to keep it on track,” according to G.H.W. Bush. The authors note: “Those who believe they have been entrusted with the inner thoughts of top leaders often proceed to act as Beijing’s messengers, urging others to have ‘greater understanding’, ‘to see it from China’s perspective’ and ‘adopt a more nuanced position’.”

Joe Biden is mentioned in the book due to his belief in the continuing utility of engagement with China, “now abandoned by many China scholars”, and the failure of his think tank at the University of Pennsylvania to mention China as a threat on its website. The authors note evidence that “the CCP has been currying his favor by awarding business deals that have enriched his son, Hunter Biden,” including an approximately $20 million share in a company founded in 2013 with the help of the Bank of China.

“This ‘corruption by proxy’, in which top leaders keep their hands clean while their family members exploit their association to make fortunes, has been perfected by the ‘red aristocracy’ in Beijing,” according to the authors.

CEOs mentioned in the book include Microsoft’s Bill Gates, Apple’s Tim Cook, Google’s Sundar Pichai, Blackstone’s Stephen Schwarzman, and Goldman Sachs’ John L. Thornton. Columbia Professor Jeffrey Sachs’ links to Beijing are also detailed.

The authors do an excellent job of discussing Chinese influence in academia. A 2018 study they cite found that 68 percent of 500 surveyed China scholars believe that self-censorship is a problem in their field. Those who fail to self-censor pay the consequences.

In 2018 the University of Nottingham Ningbo demoted Stephen Morgan from associate provost after his article criticizing the 19th Party Congress of 2017 was published. “If a university runs research projects with Chinese counterparts for profit, or depends on tuition fees from PRC students, this creates structural incentives to stay on China’s good side,” according to Hamilton and Ohlberg. “Where decision-making is centralised, individual researchers can’t push back against attempts at interference, nor can they shut down ethically dubious cooperation with Chinese institutions.”

Think tanks such as Chatham House in London, Brookings Institute in Washington, the Wilson Center’s Kissinger Institute, Elcano Royal Institute in Brussels, the German Development Institute, and the World Economic Forum come in for mention. “The China Mission to the EU … sponsors almost all think tanks working on China and Asia in Brussels, quite a few of which are headed by former EU officials,” they write.

There is a concerning historical trend of communist and authoritarian influence spreading from Russia to China and now to liberal democracies globally through financial links.

The Soviet Union actually helped found the CCP in 1921. By 2017, a CCP “Dialogue with World Political Parties High-level Meeting” drew 600 representatives from 300 parties globally. “There were delegates from the UK’s Conservative Party, Canada’s Liberal Party and the US Republican Party, with the latter represented by Tony Parker, treasurer of the Republican National Committee,” according to Hamilton and Ohlberg. Delegates signed a “Beijing Initiative” commending the CCP with “General Secretary Xi Jinping as the core.”

China’s influence in Europe

Another chapter is devoted to Europe, which is Ohlberg’s forte. It includes a discussion of former German chancellor Gerhard Schröder. He opposed the Tiananmen arms embargo against China during his time in office (1998-2005), in 1999 he visited China to apologize for NATO’s accidental bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, in 2001 he told the media that addressing political prisoners in China tired him, in 2007 he attacked Angela Merkel for meeting the Dalai Lama, and after leaving office he advised the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs on transforming the old Chinese embassy in Bonn into a traditional Chinese medicine center. He became chairman of the board of Russia’s state-owned oil corporation Rosneft in 2017. According to the authors: “Today he spends much of his time in China, brokering contacts between CCP officials and European businesses.”

In 2019, Angela Merkel ruled in favor of allowing Huawei into Germany’s 5G networks, reportedly fearing a rift in German-Chinese relations. As Germany is the most dependent on China of all European nations, according to the authors, with €200 billion in trade in 2018, a chill in relations could have serious economic repercussions for the country.

France is in no way immune to Chinese influence. French prime ministers Emmanuel Macron and Edouard Philippe have been members of the France China Foundation. A university in Shanghai employed as professors former World Trade Organization (WTO) chief Pascal Lamy, as well as former French Prime Ministers Jean-Pierre Raffarin and Dominique de Villepin. In 2005 on a state visit to China, Raffarin went so far as to endorse a law authorizing a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

The EU-China Friendship Group of the European Parliament (EP) claimed that 46 Members of the European Parliament were affiliated in 2019, though evidence indicates that this is an exaggeration. The group helps portray the CCP’s totalitarian state as a legitimate form of governance. Its leadership reportedly sought to stop the EP from inviting the Dalai Lama and was instrumental in legislation that led to €128 million in development aid to China.

Not only does China have influence at the highest levels of mainstream parties, it also makes overtures to populists like the Alternative For Germany (AfD) and Italy’s Five Star Movement. The CCP has all its bases covered, even on the right.

China’s core and periphery

The political and economic core of China is arguably the fusion of the CCP with not only state-owned enterprises (SOEs), but private Chinese companies as well. A chapter on the “party-corporate conglomerate” discusses China’s approach to “opening” its economy. “When the CCP opened up the Chinese economy to market forces it did not mean that government withdrew,” according to the authors. “It would be more accurate to see the process as one in which aspects of modern capitalism were grafted onto a Leninist state apparatus, creating a new model of Leninist capitalism.”

With the growth of China’s economy, that communist capital as it were is now fanning out globally with Hong Kong and Shanghai as hubs. The authors moot the idea that Beijing’s intention could be to replace New York and London, over time, with Shanghai as the world’s financial capital.

The book labels China’s Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) as “the CCP’s principal vehicle for promoting and entrenching the Party’s alternative discourse system for the world.” The authors note that “To the outside world, Xi and other leaders talk about ‘win-win cooperation’, and ‘a big family of harmonious co-existence’ and ‘a bridge for peace and East-West cooperation’, but in discussions at home, the talk is of achieving global discursive and geostrategic dominance.”

After signing up for BRI, according to the authors, “political leaders and senior bureaucrats soon adopt the CCP’s language, reinforcing the Party’s way of presenting China to the world, in a kind of subliminal soft power.”

A chapter on the Chinese diaspora of 50-60 million people of Chinese descent who live outside mainland China notes that “The Party has propagated a version of ‘Chineseness’ aimed at binding overseas Chinese to the ‘ancestral homeland’, in so doing mobilising for its own purposes national pride in China’s achievements.” A teaching manual for China’s influence operations is quoted as saying, “The unity of Chinese at home requires the unity of the sons and daughters of Chinese abroad.”

The most powerful and loyal of China’s diaspora are collected annually into the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), which in 2013 for example included 52 billionaires among the delegates.

According to the authors, Chinese influence operations under the aegis of the state-directed United Front, are “increasingly following the advice laid out in 2010 by a CCP strategist —build ethnic Chinese-based political organisations, make political donations, support ethnic Chinese politicians, and deploy votes to swing close-run elections.”

The case of Nick Zhao is recounted in which a Chinese spy ring reportedly attempted to recruit this Australian national by promising him A$1 million for a campaign to run for parliament. A few months after Zhao reported the incident to Australian intelligence, he was mysteriously found dead in a motel room.

China’s influence operations have been closely studied by Anne-Marie Brady at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, and her student James Jiann Hua To, whose work is duly acknowledged in the book. Clive Hamilton is from Australia. That leading scholarship on the issue of Chinese influence operations comes from down under is no surprise given that there, along with Canada, is where united front work is most advanced.

The authors report an estimated $10 billion annually spent by China on the media. This budget is geared towards expanding Beijing’s international influence as evidenced by a 2011 call by the president of the well-resourced Xinhua News Agency for a “new media world order.” The CCP takes pains to present this new order as free, but to no avail against the cognoscenti.

Employees of another well-resourced CCP-controlled media organization, China Global Television Network (CGTN), “confirmed that Beijing calls the shots,” according to the authors. “Clips of Xi Jinping with messy hair cannot be aired, and images showing Taiwanese flags are cropped.”

What’s more, China’s state media “journalists” likely conduct espionage on the side. “Xinhua employees admit to having written reports intended for internal consumption by China’s leaders only.”

Pessimism with an optimistic ending

While most of the book is pitch-perfect, there are three points where the authors overstate a sense of pessimism.

In the discussion of global governance they write: “In July 2019 Hong Kong activist Denise Ho addressed the UNHRC. Overriding interruptions by China’s delegates, she called for China’s membership of the council to be suspended. But China is too deeply embedded in the UN system for any such call to be heeded.” This is arguable. There are strategies that can be used to expel China from not only the Human Rights Council, but from the UN itself, if only democracies had the will.

After a section on Britain the authors write: “In our judgement, so entrenched are the CCP’s influence networks among British elites that Britain has passed the point of no return, and any attempt to extricate itself from Beijing’s orbit would probably fail.” This is a bit much. Boris Johnson has all but ditched the “Golden Era” of Sino-British relations in planning to phase out Huawei entirely from Britain’s future 5G network, according to a July 4 report.

The authors argue that democracies should defend their most important institutions (one would think that the UN is one of those institutions as the 1948 UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights includes free elections) but state that “Democracies won’t be able to change China.” This too is overly pessimistic. We can and must seek to democratize China in order to resolve the growing conflict that it has with the post-1945 international order. There are significant dissident and ethnic populations in China that do support democratization and could be better supported.

The authors themselves call for, or at least hint at, actions that will pressure China to democratize — exposing the CCP’s lies through media attention, boycotts, protection for people of Chinese heritage who speak out against the CCP, prosecution of those who threaten them, replacement of China’s funding of universities and media with public funding, diversification of markets away from China, and fostering of a global democratic alliance system.

And, the authors do end on an optimistic note that most will hopefully find agreeable. “Despite the grim picture painted in this book, we remain hopeful that democracy and the will to freedom can prevail.”

Anders Corr holds a Ph.D. in government from Harvard University and has worked for U.S. military intelligence as a civilian, including on China and Central Asia. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LICAS.news.

Hidden Hand: Exposing How the Chinese Communist Party is Reshaping the World, (Hardie Grant, 2020), by Clive Hamilton and Mareike Ohlberg, 425 pages. $27.