In late July, a group of Chinese government officials and academics met in Urumqi to discuss how Xinjiang was implementing a national plan to “Sinicize” Islam.

The officials did not bring up the religious sites China has demolished, the Islamic books it has burned, or the Uyghurs it has “re-educated” in concentration camps for any suggestion of Islamic belief, according to a Xinhua News agency summary of the event. Those actions proceeded under separate Chinese Communist Party plans.

But the plan they were responsible for, a five-year work outline launched in 2018, had not been fully executed: Islam itself needed more engineering, they said.

Specifically, China needed to do more to “meld Islam with Confucianism.” To achieve this, it needed to release a new translated and annotated Chinese Qur’an aligned with the “spirit of the times.”

“Sinicizing Islam in Xinjiang should reflect the historical rules of how society develops, through the consolidation of political power, the pacification of society, and the construction of culture,” said Wang Zhen, a professor at China’s Central Institute of Socialism, the event’s sponsor

The institute is part of the Communist Party’s United Front Work Group, which controls Chinese religious affairs. It produced the Sinicization plans.

Religion viewed as threat

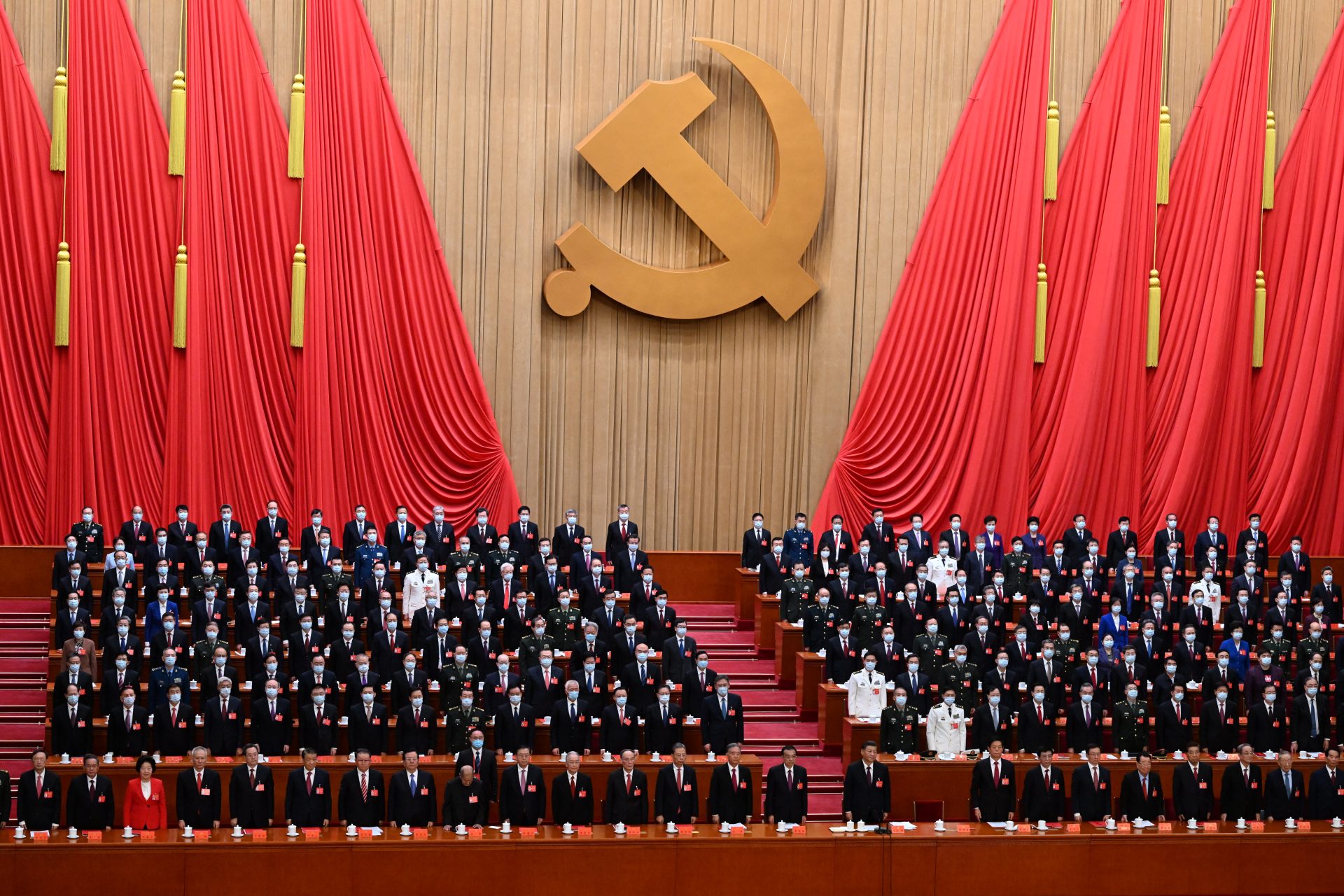

The Chinese Communist Party, or CCP, has long viewed religion – and its suggestion of any power above – as a threat to its primacy.

Over the decades, it has tended to persecute Uyghur Muslims in similar ways, under different propaganda slogans, with increasing intensity.

But today, following a campaign the United States has labeled genocide, the party has practically eliminated any public practice of Islam in Xinjiang that it does not directly supervise. It is now working out the kinks in a new version of Islam which it hopes will bind Chinese Muslims, including Uyghur Muslims, even closer to the state.

“The ultimate goal of Sinicization is to allow for that greater kind of supervision,” said David Stroup, a lecturer in Chinese Studies at the University of Manchester. “They want to bring everything under their umbrella of control.”

32-point plan

Communist Party Secretary Xi Jinping first mentioned “Sinicizing” religion in China in a 2015 speech. He mentioned Sinicizing Islam specifically in 2017.

By 2018, the party had drawn up national plans for “Sinicizing” each of the country’s three major monotheistic religions: Protestantism, Catholicism, and Islam, to be implemented over the next five years.

The 32-point plan for Islam highlighted “issues in some areas that cannot be ignored,” according to an English translation hosted by China Law Translate. Some places had been “permeated with religious extremist ideology.” Mosques emulated foreign architecture, Muslims wore foreign clothing, and the halal food label was overapplied.

“[S]ome negate the traditional ideology of Chinese Islam,” the plan noted. In response, among other measures, the party would beef up its religious personnel, “correctly explain” the Quran and Hadith in a new annotated version, and promote “using Confucianism to interpret scripture.”

“Using Confucianism to interpret scripture” references a Qing Dynasty collection of Islamic translations and writings in Chinese, known in Western scholarship as the Han Kitab, which use Confucian concepts to expound on Islamic theology. The texts were produced in eastern China, never circulated in the Uyghur region, and are not recognized in Uyghur Islamic tradition.

“The CCP is identifying this as the only correct religious practice in China,” said Stroup. “Using this kind of framing, to align Islam with Confucianism, align Islam with Chinese tradition, is a very selective reading of history.”

In addition to the Chinese translation, the party is considering a new, Sinicized Uyghur translation of the Qur’an. Many Uyghur Muslims cherish a 1980s Arabic-to-Uyghur translation by the religious scholar Muhemmed Salih.

But bookstores stopped stocking it around 2010. They replaced it with a widely criticized group translation, which sold for 1,000 yuan.

Salih died in police custody in 2018, at age 82.

“The times are always changing, society is always improving, and so our understanding of classics like the Qur’an should change as well,” said Peking University Professor Xue Qingguo, according to the Xinhua report on the Urumqi conference.