The Malaysian fairy tale is over. Two years ago, a ragtag collection of political parties trounced the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition at the polls, despite BN’s flagrant attempts to skew the vote and maintain its 61-year grip on power.

At the time unlikely hero Pakatan Harapan (PH) was a coalition of the Democratic Action Party (DAP), Parti Keadilan Rakyat (the People’s Justice Party or PKR), Islam-inspired Amanah and Bersatu, an all-Malay party.

Meanwhile, BN was a coalition dominated by the United Malays National Organisation (Umno).

Recently, Umno also cemented an alliance with conservative Islamist party, PAS, which is intent on introducing a hard-line version of shariah to the nation, including severing heads and extremities as punishment for crimes.

The latter is also reviled among the non-Muslim populous for its tacit approval of child marriage among other questionable approaches to human rights.

Yet, back in 2018 and led by enigmatic former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad, PH rode a wave of euphoria, desire for change and need to expel a BN-run system bloated with corruption and cronyism.

Despite his then 92 years, he took on a gruelling election campaign, electrifying audiences across the country. Malaysia was transfixed, with even hardened media cynics — some of whom Mahathir had imprisoned — starting to believe that an old leopard could change his spots.

Malaysians from Singapore to Australia, to the U.S. raced home, leaving notes on desks, on shop fronts: gone home to save my country.

PH destroyed BN at the polls, recording a stunning victory and prompting the country’s first change of government in its history.

As legions of PH supporters camped outside major political centres and even the royal palace, waving flags and singing songs, observers likened the event to historic toppling of dictatorships globally.

Heady stuff indeed.

Then, last weekend, Mahathir ripped through PH’s dreams in one swift stroke, turning domestic politics upside-down and dissolving the government.

The public was agog. Shock quickly turned to anger and a strong sense of betrayal.

In the run-up to this bombshell, the prime minister publicly courted Umno, the party he had once led for 22 years and from which he had quit in disgust over the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal, forming the splinter Bersatu party.

Rumours swirled that he was about dump PH to form a Malay-dominated government with Umno, PAS and rebel MPs from PKR, essentially reversing the people’s mandate, and leaving allies DAP, Amanah and the majority of PKR out in the cold.

Some BN MPs began celebrating that fact before any formal decision had been made.

Shortly thereafter, Mahathir tended his resignation to the king, Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri’ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah, and then he caught Bersatu off-guard by resigning from it too.

Result: chaos. Neither coalition had a majority, with no prime minister and one party leaderless with no idea what to do next.

Yet, disaster was always on the cards.

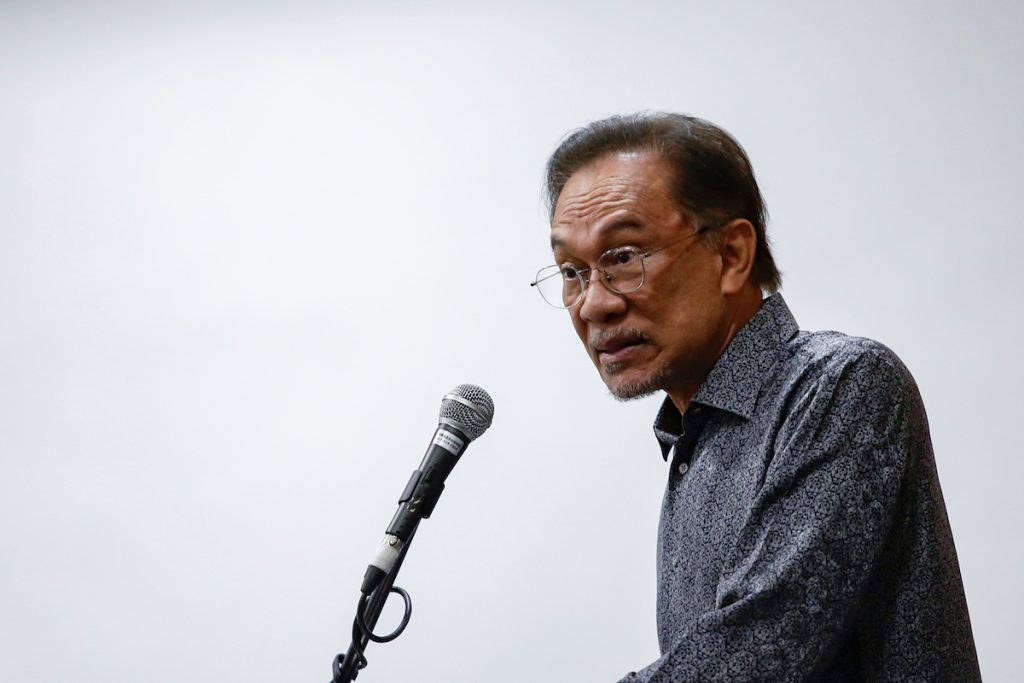

Cutting a long political story very short, in the run-up to the 2018 general election, PH needed a strong and capable leader, with Anwar — who was at that point the coalition head — still languishing in prison.

Mahathir, an elder statesman with decades of experience was by far the obvious choice, even if Bersatu was new to the PH alliance and not the largest party by any stretch of the imagination.

Added to which, there was still a deep-seated mistrust of Bersatu among the DAP and PKR ranks because it was essentially the old enemy Umno waving a different flag.

Regardless, they formed a pact: Mahathir would take over the reins during the election and become prime minister, gradually handing over power to Anwar upon his release and re-election to Parliament.

Up to that point, the two men had been sworn enemies and Mahathir had done everything he could to ensure Anwar never saw the prime minister’s office, so for them to shake hands on this agreement was nothing short of astonishing.

At the time, the public took it as read that Mahathir had put his bitter dispute with Anwar to bed for good, so that he could concentrate on crushing Najib Razak and his cronies.

Yet, Malaysian politics is based on the principle the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Mahathir had not forgotten. Nor does he forgive. Ever.

As PH settled into the seat of government, it became apparent that Mahathir had no intention of handing over power to Anwar.

Mahathir once described Anwar as “morally unfit” for leadership and did not change his tune right up to the point when they clasped palms for the first time in 20 years.

With Mahathir back in charge, rumours again swirled that he was grooming another successor — the likely candidate being Anwar’s righthand man at PKR, Mohamed Azmin Ali — or looking to form a non-partisan unity government.

More recently Anwar’s apparent crown prince attitude, letting the world know the reins of power were all but his, irked Mahathir somewhat.

The prime minister was further turned off by Anwar’s PKR party and its incessant mudslinging. Public squabbles and gutter politics were an almost daily event, as the party leadership traded blows and became divided into two clear factions: the majority backing Anwar, while a sizeable minority sided with Azmin.

The public also made its revulsion of PKR’s lack of social or even political decorum known.

BN has recorded resounding victories in recent by-elections, giving it belief that the political momentum is turning back in its favour.

On top of which, the PH presidential council nagging Mahathir to announce a date for handover appears to have been a step too far.

On Feb. 21, it all came to a head.

It is pretty clear now that Azmin approached Bersatu leaders about leaving the ruling coalition and forming a new government with the majority of the opposition, excluding Umno leaders on trial for corruption, i.e. Najib Razak and his faction.

It is a fair bet that Mahathir gave his blessing to this move, even if he could not be seen to do so in public.

So, Bersatu dropped out of the ruling coalition, Azmin and his supporters quit PKR, and Mahathir resigned as prime minister in quick succession.

The game was afoot. And then it turned completely upside-down when Mahathir quit his own party.

Somewhere along the lines, the opposition deal had changed from the most of us minus the rotten apples to: it’s all of us or not at all.

Mahathir chose not at all.

There was no way he would accept Najib and his followers, and you would have thought that his former Umno faithful would know you do not give him an ultimatum.

So, here we are. After much confusion and posturing between Mahathir and Anwar who were the prime candidates to take over, the king nominated Bersatu president Muhyiddin Yassin as prime minister, believing he had the majority of support from MPs, who appeared to switch allegiances based purely on which way the winds of power were blowing.

So, BN is back in control, along with new allies PAS and Bersatu, and experts say national politics has been set back more than 20 years.

Umno leaders, including Najib, on trial for corruption expect their cases to be dropped and PAS is eyeing senior cabinet positions, which does not bode well for the 40 percent of the country that are non-Muslim.

The once ruling coalition partners DAP, PKR and Amanah feel betrayed by Azmin and Bersatu, and the people feel betrayed by politicians, full stop.

Mahathir continues to challenge the legitimacy of Muhyiddin’s appointment (both claim to have support from a majority of MPs).

However, the whole debacle shows that, even with a clear mandate, the will of the people does not matter one bit.

The only political currency in Malaysia is power.

Gareth Corsi is a freelance journalist based in Malaysia. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.