First part: Churches in Philippines struggle to help those battered by pandemic

This is the second of three parts.

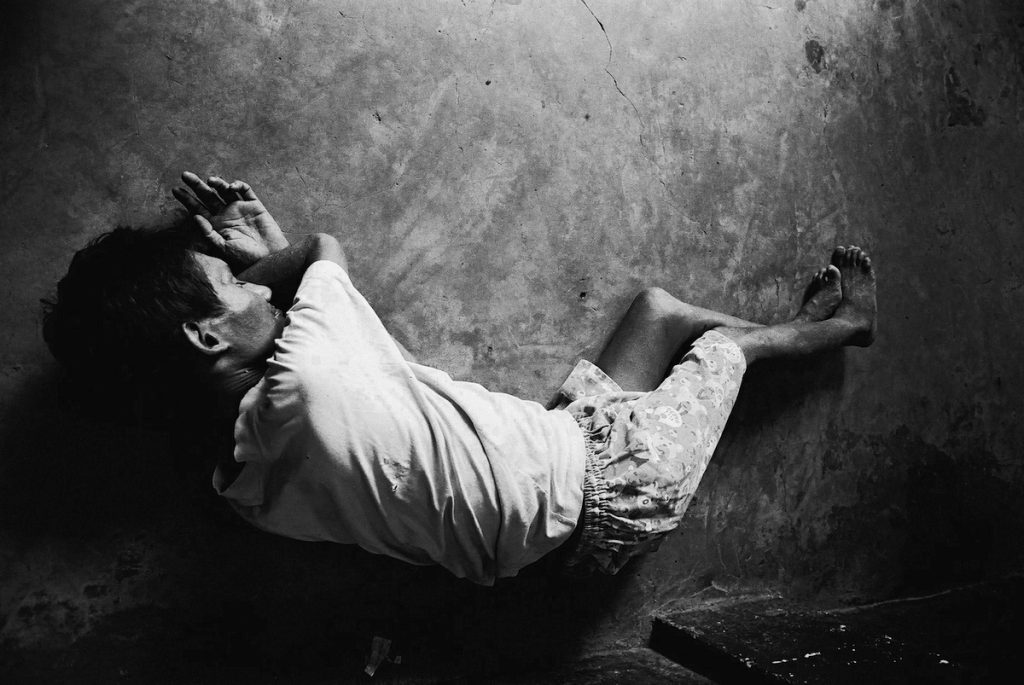

Guillermo Calderon’s kin and neighbors in the village of Bayubo, Jala-Jala town, 70 km east of the capital, call him “The Legend.”

The nickname shows fondness and exasperation for the 74-year-old grandfather diagnosed 40 years ago with schizophrenia and bi-polar disorder.

After he escaped several times from the National Center of Mental Health, the premier treatment center for patients with psychiatric illness, his family decided on home care.

It is a tough task, requiring shifts of nieces and nephews to stay in his shack in the family compound.

His niece Elsa Calderon-Carlos told LiCAS.news that Tay Emong, as Calderon is called, stopped taking his medicines about 15 years ago.

“Nobody could force him. Bringing him back to the mental hospital was useless. He always ran away,” she said.

Calderon disarmed watchers because he was never violent. An escape artist, he often wandered around the 44 square-kilometer town, even hitching rides on riverboats to visit relatives in a nearby province.

“He breaks out into curses; he can’t help it. But he has never hurt people, not even on his worst days,” said Elsa. “He mostly talks about history and the stars and the environment.”

The family tightened its guard around Calderon since the start of quarantine in March. But in the first hour of April 30, while a nephew slept, he sneaked out of the compound.

It was on the afternoon of Labor Day that a grandson, with the aid of a relative in the village council, found the old man battered and bloodied in a corner of a police precinct.

The policemen who arrested Calderon for violating the curfew were new to the town.

“The older ones know him; they would have just sent someone to us or brought him home,” said Elsa.

Police claimed that the old man fought arresting officers. But hospital medical records mentioned only minor bruises when police took Calderon there at 3 a.m.

“He had severe injuries when we got him back,” said Elsa.

Filipinos with mental health needs “suffer silently in the dark,” according to Senator Risa Hontiveros, principal author of the country’s first law on the delivery of mental health services.

President Rodrigo Duterte signed the law in June 2018. It promises affordable mental health care and bans practices that discriminate against persons with psychiatric needs.

The law also pledges “humane treatment free from solitary confinement, torture and other forms of cruel, inhumane, harmful or degrading treatment.”

Calderon’s case was the third in as many weeks to feature extreme brutality by quarantine enforcement officers toward mentally challenged people.

Police on April 21 killed Winston Ragos, a former soldier suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD.

Video footage show the former soldier with his hands in the air as people begged police to grant the family custody of the man.

Instead, law enforcers taunted the mentally-ill veteran. One of them shot Ragos when he dug a hand into a sling bag. They left him bleeding on the pavement and trained guns on people who tried to come to his aid.

Hours after, they presented a gun Ragos supposedly owned. Kin said he never carried weapons.

A week after, members of the Quezon City “discipline task force” beat up a 38-year-old mentally challenged fish vendor for not wearing a mask in a public space.

The task force later claimed Michael Rubuia tested positive for illegal drugs.

Threatened with a criminal suit for violating the rights of a mentally-ill person, they dropped the charges against Rubuia and released him to his family.

Police in the southern Philippine province of Agusan del Norte also shot dead farmer Junie Piñar earlier in April, claiming the drunken man charged at their checkpoint with a bolo.

The incident occurred a day after Duterte ordered law enforcers faced with “unruly” citizens “to shoot them dead.”

Stigma and contempt

A 2018 government report shows a critical health backlog.

There is only one public doctor for every 31,000 Filipinos needing general health care and only two to three mental health workers for every 100,000 Filipinos.

A 2014 World Health Organization report noted that hospitals allot one bed for mental health patients for every 100,000 people. Psychiatric hospitals have a ratio of 4.95 beds for every 100,000 people.

The National Center for Mental Health had to scale back operations in late April after 13 psychiatric patients and 62 employees contracted the new coronavirus disease.

Filipinos with disabilities have enjoyed discounts and exemption from value-added tax for their medicines and basic food needs for more than a decade now.

But social contempt excludes many from job opportunities, stripping away personal dignity and trapping them in poverty.

“Poor understanding of their condition adds to their dilemma, causing others to shove or ignore the problems they have,” said Dr. Noel Reyes, the center’s chief of medical and professional services.

At least 14 percent of people with disabilities also suffer from depression, the mental health expert said.

At least seven Filipinos attempt suicide daily. Intentional self-harm is the ninth leading cause of death among young adults between 20 to 24 years of age, according to the health department.

Walking with the poor

Online celebration of Masses, recollections, and prayers through church-run radio and television networks try to plug the need for spiritual connection.

But Father Gilbert Billena of San Isidro Labrador parish in Quezon City said “real physical needs” require “real physical response.”

He accompanies lay volunteers who deliver hot meals to the poor in his parish, saying it allows for counselling and consoling even with physical distancing rules.

Father Billena said the feeling of helplessness when children cry with hunger can drive parents half-mad.

Mothers have approached him, weeping over their inability to provide milk for babies and toddlers.

“We give secretly because of limited resources,” he said.

The government also frowns on the practice. Health officials insist babies should be fed from milk banks, with supplies coursed through local officials.

It is the ideal response. But grassroots leaders are already swamped with bottlenecks in food and cash aid deliveries, so that need has been sidelined.

On their daily rounds, Father Billena and Vincentian priest Danny Pilario see people walking aimlessly as they rack their brains for food resources or begging by the roadside.

“Some of them are so shabby; they have not gone to shower nor changed their clothes for weeks,” noted Father Pilario.

He said church people going out to help the poor should think beyond the government’s “stay at home” injunction. “They may need to violate it in some crucial times,” he said.

Frontline workers and aid givers also need help in battling fatigue and the distress that come when they cannot save sick people or those falling between the cracks of the country’s dysfunctional social welfare system.

Father Pilario feels a buildup of anxiety after almost two months of daily relief operation.

“I can already feel fatigue setting in. I do not know if this is still sustainable if it goes to three months,” he said.

“If this is true for me, it must also be true for the others who do more strenuous task like the doctors and nurses,” said the priest.

Like medical workers, aid givers also struggle with the fear of infection. “If this virus is in the air, we have a daily exposure to it,” said Father Pilario.

Rest is a great healer for the priest, as are days off for silence, music or prayer.

“But I also attend weekly evaluation meeting with women-leaders,” he said.

The gritty womenfolk, many mothers, wives and daughters of drug war victims, sew masks and physical protective gear in the parish. These are later donated to hospitals.

“I know they are also tired. But I am infected with their positive energies. I told myself: If they never surrender, why should I? They keep me going,” said the priest.